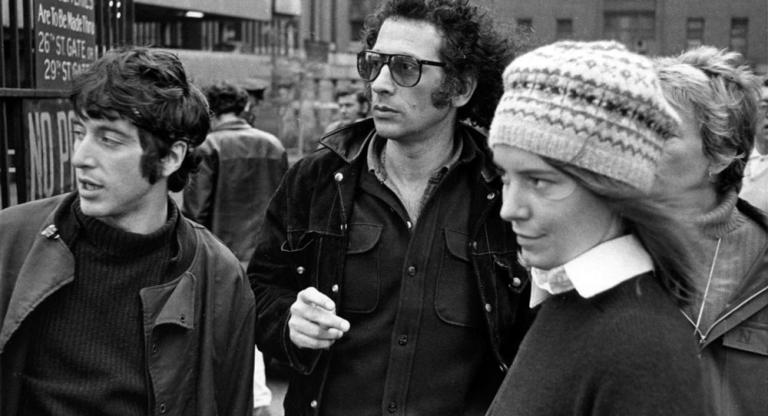

Michael Roemer is known for only two films, both masterpieces: Nothing But a Man (1964) and The Plot Against Harry (1971). Each was barely released, quickly forgotten, then revived to great acclaim in the 1990s before fading from circulation once again. Roemer, now ninety-four and living in Vermont, was born in Germany in 1928 and fled the country in the Kindertransport with other Jewish children when the Nazis came to power. He spent his teen years in London as a refugee, then came to the US in 1945 to attend Harvard.

An early associate of the trailblazing midcentury directors and cameramen who made up the direct cinema movement in documentary filmmaking, Roemer instead gravitated to fictional drama. He debuted as a feature director with Nothing But a Man (1964). Starring a mostly Black cast and set in Alabama, but partially shot in New Jersey to avoid harassment from Southern racists, the film quietly and subtly follows the budding romance between a railroad “section gang” worker (Ivan Dixon) and a preacher’s daughter who teaches school (the jazz singer Abbey Lincoln, previously seen on screen only in Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It, 1957).

The Plot Against Harry (1971) came six years later. It is a sparkling, Fellini-esque gangster comedy of Jewish despair, in black-and-white like Nothing But a Man. Roemer withdrew the film before it had a proper release because early audience reaction was very negative. Perplexingly so—the film is a high-water mark of American cinema, a jewel found in the grime of New York City as it entered its worst decade before this one.

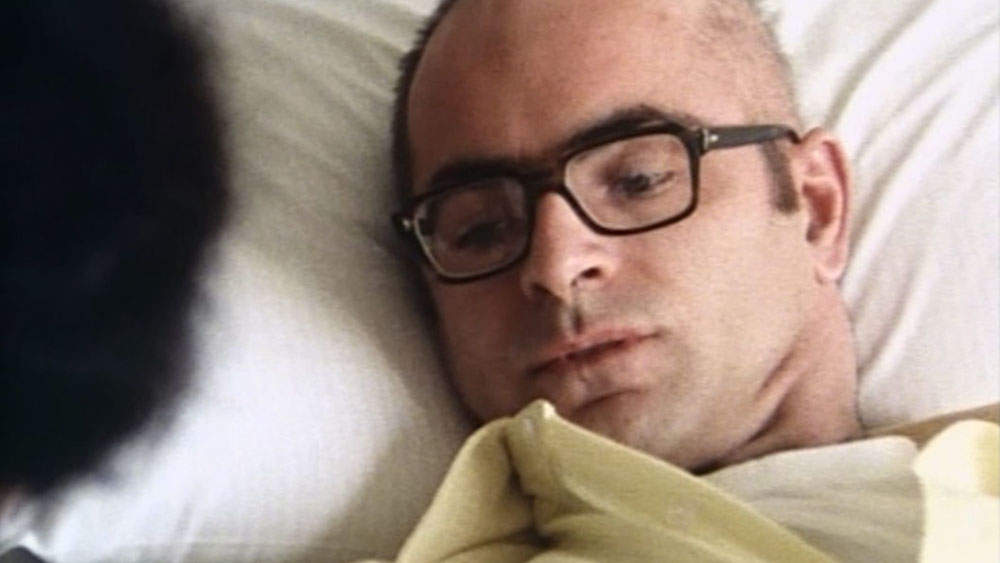

The rediscovery of a third Roemer feature as good as the others is a cause for celebration, and something of a miracle. Vengeance Is Mine (1984) debuted on television as part of PBS’s American Playhouse series, where it was broadcast under the title Haunted. It got one bad review, in the New York Times, and disappeared. Now, courtesy of The Film Desk, Roemer’s color melodrama, a study in familial anomie in New England, will make its theatrical debut in 35mm at Film Forum. Its superb cast features Brooke Adams (Abby in Malick’s Days of Heaven, 1978), Trish Van Devere (Claire in the creepy cult horror film The Changeling, 1980), and Ari Meyers, who went on to sitcom success as one of the daughters on Kate & Allie (1984–1989).

I spoke by phone with Roemer in Vermont. He speaks in a charming Old World accent, but we had a bad connection and my phone call app failed to record our first conversation. Roemer is no stranger to second takes and second chances, so we spoke again the next day. Our conversations have been combined and edited for space and clarity.

A. S. Hamrah: In rewatching Nothing But a Man right after I saw Vengeance Is Mine, I noticed the resemblance between Brooke Adams, who plays the lead in Vengeance, and Gloria Foster, who plays the father’s girlfriend in Nothing But a Man. One wouldn’t think of these two actors together, or that the parts they play in these two films of yours are similar, yet they both have the same look of worry or apprehension, or even bitterness or anger, on their faces. They both exist within a kind of sadness that is so apparent on screen.

Michael Roemer: No, I would never have thought of that. But I trust your perception, so undoubtedly there is something there. That is why I cast Brooke Adams. There is something sad in her, a sadness is always in Brooke’s face, though she doesn't come across that way in life. It was there in Days of Heaven. I certainly was aware of the sadness in both Gloria and Brooke, yes. You know, it doesn't take a lot to scrape up the happy face we put on in life. Because nobody wants to be around somebody who is not cheerful, right? I think this is in the human condition, what Brooke’s and Gloria’s faces express. It's in a great many of us, you know, at all times. And we learn to disguise it.

ASH: The reason I ask you about this is because of the style of acting in all your films. It's so low-key and subtle. And even when there are outbursts of great emotion, it's still tamped down compared with how it would be expressed in most American film drama, where it is often histrionic or performative. This is something that's clear through all three of your features that I’ve seen. How do you imbue your films with that kind of subtle energy that builds so strongly and is so different than in other movies?

MR: Well, I want the films to look persuasive. I wanted surfaces of the films to look like everyday life. And in everyday life, I think people try to hide things, but they don’t know they are doing it and what that looks like. I want strong feelings to be in the films, yes. But I wanted the audience to know them and find them and feel them without having them shown by the actor. I think feelings are stronger if they're not dictated for the audience. That's why in my films the music and all of the songs are usually source music rather than music that's composed and put in on top of the film.

I mean, I don't want to feel for the audience. I want the audience to do its own feeling. And I'll give them the material to do that, but I don't want to spell it out. Of all people, Ronald Reagan once said that the actor must never steal the tears of the audience. Some people might laugh at something that somebody else might cry about. In life, you know, some people are not even going to notice that somebody else is sad. People must have their own responses, not mine. I put things out there. And I think they're probably going to feel what I do. But I mean, nobody laughed at The Plot Against Harry when it came out. Nobody thought it was funny. I went to screenings with people who were entirely friendly to the film. And they came out and said, “Why did you show us that? It wasn't anything.”

ASH: The initial reception of The Plot Against Harry is one of the great mysteries in the history of American cinema. It's a film in which every frame is funny. Even something that's melancholy, like the interstitial street scenes, the way they are put together makes the rest of the film funnier. Something you mentioned to me yesterday was that the theme of your films is that life is hard. You mentioned your ideas on that had evolved, that when you made Nothing But a Man you held the idea that people could succeed in this country, but after it came out, that wasn't really something that you felt was true anymore.

MR: I came from a background where that was not possible. My ethnic background was one where, you know, millions of innocent people, totally innocent people, were killed. And I wasn't. So it was not hard for me to think life is potentially tragic. Then I came to the United States, and I had already lived in England for six years, and I adopted a positive view of my own role in life. I thought that I was finally free and that if I worked hard I could achieve what I wanted to achieve. And everything in the United States supported that perspective. I came to the United States in 1945, and went to university and, you know, I got used to believing that if I worked hard and believed in what I was doing, then things would work out. And then I got into the movie industry. I was paid to work on documentaries, and it wasn’t that I believed in the movies, these were jobs, but I loved them. I was learning how to make movies. And I was always aware that I wouldn't really be making West Coast movies. I enjoyed seeing those, they were fun, but I didn't believe in them. And I hope this doesn't sound pretentious, but I was serious. And I had seen people suffer. And I wanted to make a different kind of movie. And I was learning how to do that, and I was very optimistic about it. I suppose I still am in some strange way. But when I saw Nothing But a Man, which I had just made at the time, I said, this isn't true to my experience. It's true to what we, as Americans, want to believe. Politicians are always telling us if we want something, if we're unified, there's nothing we can’t do. We can go to the moon. But there is an awful lot to be done that we don't do and that they don’t ever mention.

ASH: Yet Nothing But a Man doesn’t have what you would call a conventional happy ending.

MR: But he’s such a good guy. So if he does everything so well, and his wife does everything so well, there are no flaws in them, you know?

ASH: Ivan Dixon, Duff, does get violent towards Abbey Lincoln, Josie. He hits her and pushes her to the floor.

MR: That was just one moment. Yes, he does do that. For one moment. He also breaks the chair. And he kind of tortures their cat at one point. It was just enough to say, ”OK,” you know, “this man has a few problems.” But all in all, he’s so perfect. And Abbey says all the right things, you know, to the point where he finally gets angry at her. That's what bothered me. I'm not that. I'm not that good a guy. I mean, how we see ourselves and what we really are are two different things. I saw myself selflessly until I was watching the character of Duff Anderson in my film, and then I didn't see myself that way. I didn't think it was true. Look, I think if it had been a white guy, he wouldn’t have been accepted as real. Because, you may completely disagree with me, but he’s too honest, he’s so much the perfect American male, you know?

ASH: You said if he were a white guy Paul Newman could have played him?

MR: I mean, Paul Newman was always playing a little bad, but he was also ultimately the one good, honest guy in the movie at that time, in the 1960s. For instance in the sequel to The Hustler from the 1980s, The Color of Money [1986]. If you see George C. Scott in the first film, this is what Newman would have become. Now in this other one, he is losing on purpose and helping people get married. It’s the opposite of the other film. It’s a fantasy of the good American man.

ASH: I see what you mean. Let’s talk about what happened after you made Nothing But a Man. You made The Plot Against Harry five years or so later, but it was not released in 1971, as it was supposed to be. Then, more than ten years after that, how was it that you came to make Vengeance Is Mine for PBS television in 1983? What had happened in the dozen years between the two films?

MR: I made a film called Dying [1976], which—while making it—became for me a deep involvement with people who were facing death. It was a documentary. And that changed my life. As you know, a film, if you mean it, is everything while you are making it, and that is going to have consequences. Also, I had started thinking about screenplays, and I knew that, with The Plot Against Harry, it was no way forward for me at that time. I thought then it was too fragmented in the screenplay, so that to fragment it, or the central figure, even further, to disconnect him further from other people and from what is going on around him—you know, he's totally out of touch. And I couldn't go on in that vein. There was no way of going forward, though I tried. I personally think that Quentin Tarantino had the same problem after Pulp Fiction [1994], which is also very fragmented. I thought it was a great film, but he went back into genre and made Jackie Brown [1997]. I couldn't do that, because I don't believe it. But he was willing to do that. And I couldn't, because I have to believe it. I couldn't do a film that I didn't believe.

ASH: Then how did you go from making a documentary like Dying to making a return to dramatic fiction?

MR: After The Plot Against Harry, I spent two and a half years writing a story that the grandson of two big and well-connected, famous Hollywood producers, who was himself a producer, wanted to make. He was a very nice guy. He loved that script. And he said, “I want to make that film.” And I said, ”Fine,” you know, “I'm glad somebody wants to do it.” And he called me from California at four in the morning, seven o'clock our time, and he was going to set it up with a small Hollywood company that was making exciting new films at the time. I don’t want to mention these names. They made films that people still watch to this day. They were known to be independent-minded. And they sent the script back to him, and said, “Are you crazy?” I still think it's a good script.

ASH: Was this the screenplay that became Vengeance Is Mine?

MR: No, no, no, Vengeance Is Mine was later. There was a program on public television, and I thought I was qualified to be part of it. And I went to see the producer. And she read my screenplays, one of which was Pilgrim, Farewell [1980] which I eventually made right before Vengeance Is Mine, with Christopher Lloyd in it. She read these, and she said, “You don't know how to write a script!” And I said, “Why not?” I thought I did. And she pulled a scene out of one of the scripts and said, “What does this mean?” She was angry at me! Though PBS did end up debuting those films.

ASH: Producers get mad at the strangest things. What was the genesis of the story of Vengeance Is Mine? Why did you choose at that time to turn your attention to these more middle-class and upper-middle-class, kind of semi-bohemian people in summertime New England? They seem a fairly long way from Black railroad workers and school teachers in Alabama and Jewish gangsters and caterers in the New York suburbs.

MR: I began with an image, which is usually how my stories begin. I didn't know anything. I had an image of a woman, Donna, the married woman in the film who Trish Van Devere plays—George C. Scott was her husband, by the way. She is about to be divorced and she is looking into her own house at night. And she sees another woman, a younger woman, in bed with her own child, a teenage girl, together like they are mother and daughter. I had no idea who they were. And the film evolved out of that image. But that image is not in the film.

ASH: Jo and the daughter, Jackie, are together in Jackie’s bedroom, though. And there is the scene where Donna looks in on Jo, the Brooke Adams character, in bed with Donna's husband while he is sleeping, in which nothing is happening between them, but Jo has got in bed with him just so Donna will see them together.

MR: That is close. But I think I never even connected those. You realize, of course, when seeing that scene, that the whole thing was directed by Jo to be an image she plants in the married woman's brain. It’s not really true. She puts it in her head. It's a very awful thing to do. And so Donna also feels that this new woman is also taking over the life of her fourteen-year-old daughter, and she’s very angry, and she begins to haunt her own family as she is being eliminated from it.

ASH: When you put it that way, the film develops an Ingmar Bergman quality that I noticed between the two actresses. Trish Van Devere is a Liv Ullmann character and Brooke Adams is like Harriet Andersson. Were you thinking about Bergman when you wrote it because it has that kind of . . .

MR: Psychological element? No, but I think we both came out of Strindberg. Bergman, I think, was very influenced by Strindberg, and of course we're both Europeans. But I wasn’t ever influenced by Bergman at all. I had problems with his movies, actually. Because they were so explicit, so full of symbols. There are so many symbols! I don't like symbols.

ASH: It's true your films don't resort to symbolism. Also, the way you use real people and real locations is unique. One of the remarkable things about Vengeance Is Mine is how it really gives a feel of this town in New England, and life on Block Island in the same way that we feel the presence of Alabama in Nothing But a Man, and New York City and its suburbs in The Plot Against Harry.

MR: Well, we are where we are, we are who we are, and where we are is not all that separate in my mind. You don't live separately from the room you're in and all the other people around you outside of it. I would say I am influenced by documentary filmmaking. My friends from when I was a young person were documentary filmmakers, Fred Wiseman, Albert Maysles, Ricky Leacock. And I said to myself, “If I can’t make something that looks as true as what they're doing, then it's not worth doing.” Fred Wiseman, we were both in Boston. I knew him before he produced The Cool World [1963], and before I made Nothing But a Man. We were on the same page about many things. And he liked what he’d seen of my work. And I love Titicut Follies [1967] and Hospital [1970].

ASH: The documentary aspects of your work are clear, but you add so much more with the actors you choose. You were telling me about how you cast the actors in The Plot Against Harry. These are people one doesn't see in any other movie.

MR: We didn't have enough money to sign with SAG. So I had to find actors who were either not in SAG, or were so infrequently employed that nobody cared. I don't think Martin Priest—who was in Nothing But a Man, in a small role as a racist, and then in The Plot Against Harry as the main character—I don't think he ever was in any other films. He was great, he was as good an actor as Robert De Niro! The man who played his brother-in-law in Harry, Ben Lang, he was not an actor, but in the 1930s he had wanted to be an actor, but he came down with tuberculosis and couldn’t go into it. And the rest were people I’d met in amateur theatricals. Many of them were attached to temples.

ASH: Ben Lang has a stolid-yet-tilted quality that gives him an original presence as a character actor. He has a quizzical aspect even when things are going very wrong, almost like he’s laughing at Harry. You mentioned that you felt Martin Priest was very angry and almost resentful, even before you cast him in the lead role.

MR: Yeah, that was his way of saying, “I don't care whether you cast me or not.” He came in, and he said, “You're not gonna cast me, I know you're not.” And I remember laughing and saying, “How do you know?” I understood what he was doing. He was daring me and downplaying his abilities. And I thought, I can use that quality. He had been a student of Strasberg. He was a Method actor. He said, “Most people just won't hire me.” And actually there was someone in New York who came to me and said that I should not hire him. He had a bad reputation. I spent the year that I was working on that script having lunch with Marty once a week. And there were little things, like when he makes that Donald Duck voice. He did that once and I said, “Hey, I think we'll use that!”

ASH: I noticed in the movie, you give the backstory about Ben Lang's tuberculosis to the Harry Plotnick character. He says he had tuberculosis when he was a child.

MR: I don't remember that. But you've seen the film recently, and I haven't. I tried to get things from life. I mean, I have to say that almost nothing in Vengeance Is Mine is truly mine. I heard people say those things. I didn't make them up. As far as I'm concerned, it's all factual. To invent doesn't mean you make something up. It means you come upon it. That’s what writing is. I can't invent anything. Nothing is going to be better than what actually exists.

ASH: Do you think that's why, when you first showed The Plot Against Harry in 1971, people didn't know what to make of it? Are they seeing themselves in it and rejecting that?

MR: I have no idea. I know that people didn't find it funny. The main thing I remember is that nobody laughed. Nobody laughed, literally no one. And there weren't that many screenings. I mean, it was so discouraging. I just thought I'd made a terrible mistake. And I'd gotten a lot of people to work very hard, very long hours of their valuable time for almost nothing. The actors didn't get anything out of it. They never made money from it.

ASH: Did the actors see it when it played in the New York Film Festival in 1989 and finally got a real release in 1991?

MR: Yes. Oh yeah. They saw it. All except the woman who plays Millie, the younger daughter [Margo Ann Berdeshevsky]. She was in Paris at the time. All the other actors were there at the festival in Lincoln Center. Wonderful. We had such a nice time there. I think Ben Lang was disappointed that the film didn't get shown at the beginning. I don't remember what he thought of the movie then. When he and the others saw it, they loved it with the whole audience who saw it on screen in the festival.

ASH: Your ability with those actors was so wonderful and so confident.

MR: I had a wonderful teacher, a man who taught me a process, how to work, not what to achieve, you know, not an end result. But how to work. And my closest and oldest friend, Frank Auerbach, was a painter. And he was at the same school. And he said the same thing about learning about painting. In other words, it was not limited to acting. The man was a man of the theater, who taught us. And I could never have directed without him. I was very confident about directing Nothing But a Man. But first, I had to write it, you know? You can't separate directing from writing. I can't. It's one. It's one process. And a lot of people told me when they read that script, “This is not working. There’s nothing happening.” And I said, “Yes, something is happening.” I remember, very importantly, a figure involved in Nothing But a Man who helped us make the film called, he called me and said, “The actors are not acting. They're not acting.” He was angry at me. I said, “Yes, they are.” And I was so sure. I knew how good everybody was in the movie. I knew that it would work.

ASH: You were right. Before we go, there’s something I was wondering. In The Plot Against Harry, Harry’s last name is Plotnick. And in the credits of Vengeance Is Mine, there is a large number of people on the crew with the last name Plotnick. What’s with all these Plotnicks?

MR: Well, there are a lot of Plotnicks there. I have— I had, unfortunately he died, a good friend named Stan Plotnick. He was someone who saw the Dying documentary. And he called me. He had been an accountant at the film lab. We knew each other, didn't know each other well. But he called me and said, “If you ever want to make another movie, please let me know. I want to be involved.” And so he got involved with Vengeance Is Mine as a producer. And Pilgrim, Farewell, the other American Playhouse movie. He and I put those together out of money from Germany and from the National Endowment for the Arts and money Stan raised from investors. You know, not very much money, but enough to make the movies. And then Playhouse got involved when it was all done.

ASH: And so the Plotnick family worked on Vengeance Is Mine?

MR: Yes, but none of them had anything to do with The Plot Against Harry and Harry Plotnick’s name. Harry got his name from a cat that my wife was taking care of when I first met her in 1951. She was taking care of two cats for a friend of hers. And one cat was called Plotnick. I thought that was a great thing. So I used it as Harry’s last name. And when I and Stan and Charlotte, his wife, who also worked on my films . . . it got to be everybody who could work on them worked on them, because we couldn't pay people very much. My students worked on those films, too. The cameraman was a very old friend of mine, Franz Rath. We met when he was nineteen and I was twenty-three. And we traveled all over the United States together on a movie. He shot a whole series of educational films I made. But he was not a Plotnick.

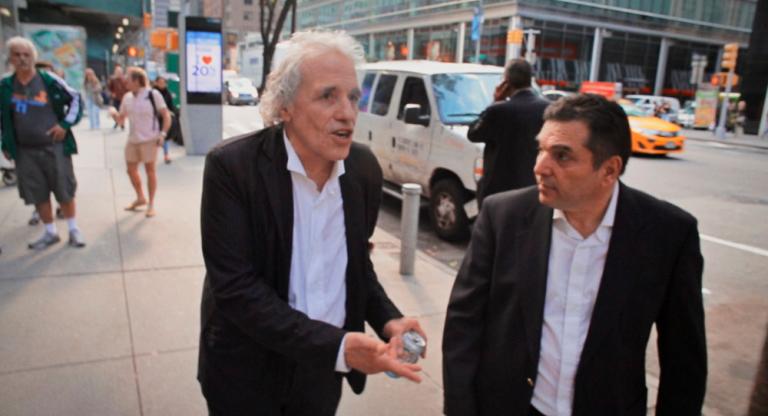

Vengeance Is Mine screens May 27–June 2 at Film Forum on a new 35mm print. Director Michael Roemer will be in attendance for a Q&A on May 27.