A cluster of threatening samurai emerge from the trees and encroach on a modest country home in rural Japan. As the men pillage the house, stealing food and water, they violently rape and murder the two women inside: Yone (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law Shige (Kiwako Taichi). Setting fire to the home, the group make their escape and the disturbing scene ends with a long shot of the billowing smoke enveloping the bamboo grove. Just as the atrocities of war emerge from the environment, the remnants of its destruction return to the natural world.

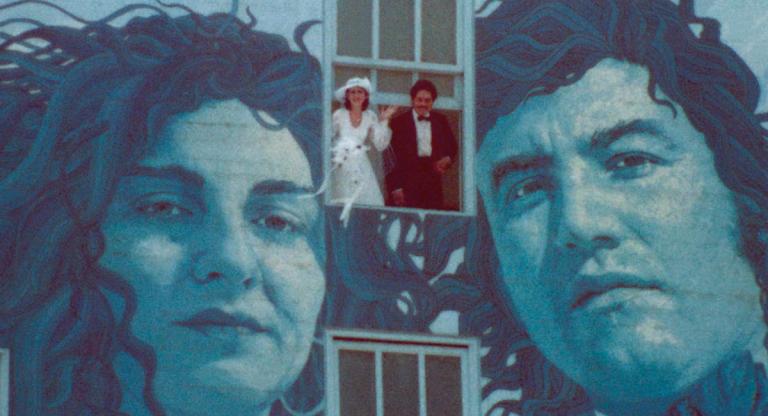

This striking introduction to Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (1968) gestures at the core thematic fascinations in his work, namely women’s struggles, wartime, and class conflict. In this historical folk horror film, Shindo follows the vengeful spirits of Yone and Shige as they hunt and prey upon samurai. Their mission is to drink “ the blood of every last samurai in the world” and feed their souls to the underworld; they accomplish this through ritual seduction. The film’s reinvestment in mythology and its poetics of expression—women do not speak about their trauma in Kuroneko, but gesture toward it through their dances, spells, and ceremonies—explores post-war trauma through a gendered lens. During the first seduction, the camera holds on a medium-wide shot of a samurai and Shige in an embrace. Suddenly, the camera pans to another plane where Yone dances to the beat of a drum. As Yone hypnotizes the men with the dance, the camera floats around her, as though moving between physical and spiritual realms. The area where she dances, the engawa, is an open-aired veranda where the natural world of bamboo trees and foliage surround the artificial contours of the house. Her stage is undefined, it is both inside and outside, material and immaterial. Shindo’s exploration of female perspectives is characterized by this abstract imagery and camera positioning. His embrace of ephemeral practices like dance, music, and spiritual rituals are reflected by abstract camera movements. The camera ultimately becomes its own subversive object which floats, tracks, and spins, subverting traditional viewing positions imposed by the conventional cinematic gaze.

Shindo’s approach contrasts Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1951), which was loosely inspired by the Ryūnosuke Akutagawa short story “In a Grove” (1922) that inspired Kuroneko’s title. While both films use unreliable narrators, fragmented storylines, and emphasize the power of memories and magic to explore the national trauma imposed by World War II, Kuroneko displays a renewed interest in womens’ lives, which was notably lacking from the era’s dominant Japanese cinema. Shindo’s film explores the perspective of women on the margins of society; rather than justify Yone and Shige’s actions, he sketches a complex and nuanced portrait of them.

Kuroneko screens this afternoon, March 1, and throughout the month, at Film Forum on 35mm as part of the series “Japanese Horror.”