“Does the penis still reign supreme?”

“Absolutely.”

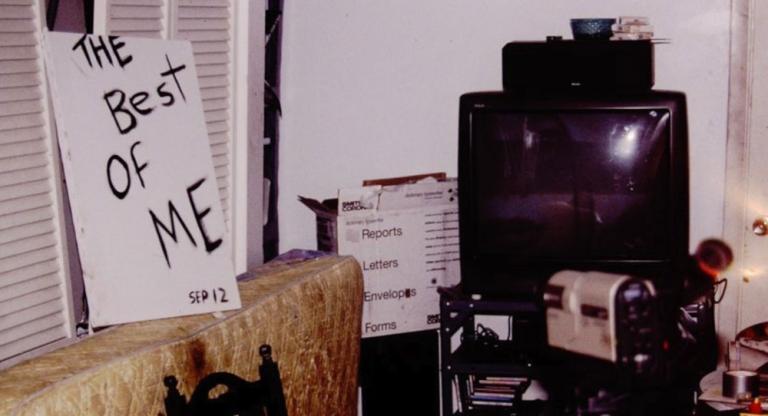

This exchange between gay journalist Arthur Bell and bathhouse proprietor Michael Fusco distills the pleasures and pitfalls of The Emerald City, a twice-weekly community access show that ran on Manhattan Cable’s Channel J from 1977 to 1978. The show blended interviews with notables from culture, law, and politics; on-the-ground reporting of events like the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade; drag, cabaret, and theatre performances; and silent shorts and cartoons, just for fun. Interviewees included John Waters, Divine, Wakefield Poole, cabaret legend Baby Jane Dexter, Charles Ludlam, and, in one of the most-viewed episodes, Quentin Crisp in conversation with Father John Noble of the gay Church of the Beloved Disciple.

Made by the maybe too-proudly monikered Truth, Justice, and the American Way Productions, the “world’s first television show for gay men and women” unsurprisingly privileges the former. When women do appear, it’s usually as satellites to gay male culture: civil rights lawyers, iconic cabaret and Broadway performers, or Monty Clift biographers; an interview with National Gay and Lesbian Task Force director Jean O’Leary is a welcome exception. Still, like Samuel R. Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999), or Faggots (1978) by Larry Kramer (he makes an appearance too), The Emerald City is an invaluable document of a pre-AIDS, pre-Koch New York gay community wrestling with the identity crisis brought on by newfound, and hard-won, respectability.

As a New York Times profile of the show explains, “The conservative homosexual is not likely to appreciate material aimed at more militant or flamboyant types.” Much of the program’s charm comes from leaning into that tension, which it thankfully never attempts to resolve. It’s front and center in the bathhouse episode, when Bell ties himself in knots to avoid the word “sex” (at one point resorting to my new favorite euphemism, “push push pow pow”), and when the owners assert that their clean, graft-free bathhouses are a natural result of an increase in gay pride: “as we feel better about ourselves, we demand better facilities.”—and, as countless corporations have since gleaned, shell out a lot more cash.

Yet the penis reigns supreme, above all in the wonderfully shaggy, campy commercials for local gay businesses like Mandate magazine (“For men who walk on the WILDE side!”), Ice Palace 57 disco (“The total nocturnal experience!”), Café Espresso in the Broadway Arms Baths (“Home of the Queen Burger—the place where you can get a good piece of meat anytime!”), and Man’s Country baths, a paradisiacal-sounding ten-level facility on West 15th Street that featured a gym, faux prison cells, and a real red semi-truck (“Come and develop your body, or a friendship with someone else’s! Visit us once and you’ll come again and again!”). The ad for the US premiere of Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane at the Quad Cinema, an Emerald City fundraiser, consists almost entirely of writhing men.

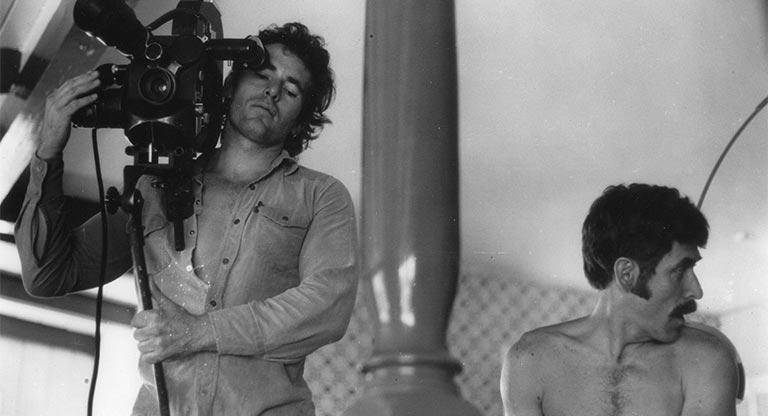

The most important artifacts, though, are the candid interviews with gay luminaries at the height of their abilities, most of whom would soon be lost to AIDS. Among them is Arthur Bressan, Jr., who would be canonical had he not pursued gay and/or pornographic subjects in his films so single-mindedly. Mid-30s, hair past his shoulders, cool as ice and sporting a killer moustache, he effuses about Harvey Milk selling tickets out of his store to the premiere of Bressan’s pride documentary Gay USA (1978), and of the film’s “educative shock—in a nice way,” all while looking forward to a long career making crossover hit gay films. It’s almost unbearably poignant to watch from this side of the gathering darkness.

Episodes of The Emerald City are available on YouTube.