In the years following Bruce Lee’s untimely death in 1973, the absence of the first global Asian superstar left a lucrative void that producers throughout Southeast Asia were ready to fill. Throughout the ‘70s, lookalikes with pseudonyms like Bruce Li (real name: Ho Tsung-Tao) and Dragon Lee (Moon Kyung-seok) starred in low-budget films that gleefully rode the dragon’s coattails, often tricking gullible audiences into thinking that they were paying for the real thing. Some of them grew deep misgivings about their “clone” identities… and then there was Bruce Le. Of all the Lee-a-likes, none copied the master’s mannerisms more closely and wielded them so aggressively, and none has had a career as eccentric and durable.

Born in Burma in 1954 and raised in Hong Kong, Wong Kin-Lung was a stuntman and bit-part actor for the legendary Shaw Brothers, but felt stifled by the studio. In 1976, he first brought his convincing Bruce Lee impression to two independent productions, The Big Boss Part II and Bruce’s Deadly Fingers, the latter of which paired him with Lee’s former co-stars Nora Miao and Bolo Yeung. From there, working with exploitation producers Joseph Velasco and Dick Randall, he churned out a dizzying stream of potboilers: Bruce and the Shaolin Bronzemen (1977), Enter the Game of Death (1978), My Name Called Bruce (1978), The Clones of Bruce Lee (1980), Return of Bruce (1987), and many, many more. Though made in Asia, these films were aimed at undiscriminating international audiences. The U.S. release poster for Le’s The Young Dragons (1974), for example, boasted the tagline: “Held in China and never before seen — BRUCE IS BACK! IN HIS 1ST FILM AT 18.”

To be clear: we love Bruce Le and his films. The nose-thumbing, the battle cries, the fancy footwork… nobody could capture the real Lee’s once-in-a-lifetime charisma, but Bruce Le brought a turbocharged enthusiasm to his mimicry that makes him irresistible company. When he became a director, he delivered shameless crowd-pleasers like Challenge of the Tiger (1980), which opens with co-star Richard Harrison playing tennis with a topless woman, and peaks a few minutes later with Bruce fighting a real bull. Where the real Bruce Lee approached cinema as a pedagogical tool for his philosophy of martial arts, Bruce Le delivered action, action, and more action—sometimes silly, sometimes sloppy, but lots of it.

As the demand for Bruceploitation dried up in the ‘80s, he went wherever the market led him, from the Philippines to Cameroon to the Great Wall of China (where he filmed the spectacular climax of his 1987 film Ninja Over the Great Wall). In 1992, he directed a lurid Category III shocker called Comfort Women, about sex slavery in the Second World War, and then one last action film, 1994’s internationally-shot Black Spot. More recently, he revisited the subject of Chinese comfort women for 2014’s The Eyes of Dawn, a more sober production for the mighty China Film Co., Ltd. He remains active in the Chinese film industry, where he hopes to mount a return to his classic kung-fu movie style.

For decades, little information existed in the English-speaking world about Bruce Le and his fellow clones. That has changed with the release of Enter the Clones of Bruce (2023), a new documentary from Severin Films that comprehensively explains the Bruceploitation phenomenon, and features interviews with all of its major onscreen players. Its makers spent six years pursuing Bruce Le (as he is still professionally known) for an interview, and he’s now an enthusiastic ally of the project, having joined the filmmakers on a four-city U.S. promotional tour in April. It was his first visit to this continent since 1983, and his first-ever trip to New York.

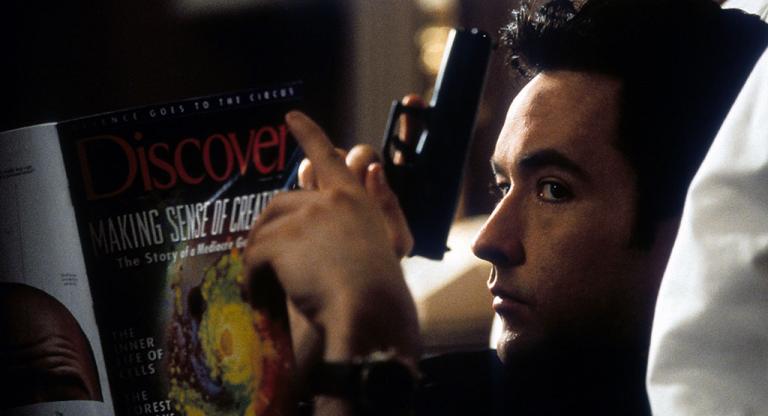

We met Bruce Le on the Manhattan leg of his trip, shortly before an Alamo Drafthouse screening of Enter the Clones of Bruce and Challenge of the Tiger. In his hotel room, Bruce was joined by David Gregory, the head of Severin Films and director of Enter the Clones of Bruce, as well as the actor and filmmaker Michael Worth, who is also the English-speaking world’s leading Bruceploitation expert. Both of them assisted with details. In conversation, Bruce alternated between English and Cantonese with the help of Frank Djeng—a co-producer on Enter the Clones of Bruce—who served as translator. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity, but we have tried to remain true to the force of his personality.

Will Sloan: We just watched your film Ninja Over the Great Wall. The scene at the end, which you filmed on the Great Wall of China, is really remarkable. How was that coordinated?

Bruce Le: Before, I was in Hong Kong—many movies. So one day I suddenly think, “I want to make the movie on the Great Wall.” I fight in the Colosseum, I fight in Paris, I fight in Africa, anywhere, but the Great Wall, which I think is the best. I wanted to go to the Great Wall because to many people it's very difficult. But the government is, you know… [It’s my] first time going to China, so they give me a very good chance to do it. So we shoot on the Great Wall—you can see the Great Wall, the last [place] they fight. It's not impossible. Nobody can do it, you know, but it’s my idea. I always find something new! My idea.

On the Great Wall, you know, I lit up a lot of fireworks. It looks like it’s a dragon. I give this idea to the government. “Oh, this fight is good—fight on the Great Wall with the Japanese ninja, Japanese samurai, we fight.” The Japanese general [in the film], he said, “I want to fight your kung fu master in the Great Wall. I want to kill you on the Great Wall.” So it's a good idea to think about how to shoot on the Great Wall. One of the producers, the production manager, after they finished The Last Emperor—[it was] shooting at a Beijing studio. Oscar.

WS: Huge movie.

BL: Yeah, yeah. He saw [Ninja Over the Great Wall], he's surprised: “How can you do it? Bruce, you're a small company, Guangxi—how can you do it?” So he always talks with me: “Bruce, can you help? You want to make movies? We have a studio, we have a big one with anything, you know.” So the second movie I do for him, Black Spot…

Justin Decloux: We’ve seen it too—we watched it today.

BL: Fantastic movie. There were many problems... They give me anything. They said, “Bruce, you shoot in here—my Beijing studio is the best in China! We made The Last Emperor. My crew is the best in China! You do for me, okay?” I said, “Okay, So what kind of story?” I said, “Okay, make Black Spot.” I read [the premise] in a new book. I said, “Oh, that's a good idea. I’ll shoot it.” So after that I called Dick Randall; I called my friend in Paris; they helped me. I go to Italy, then Paris, and then Hong Kong, and go to the Golden Triangle to shoot this movie. Nobody can do this movie in the whole of China.

WS: The scope is huge for what it must have cost.

BL: Yeah, the tanks and the helicopters…

JD: You’ve shot everywhere—in South Korea, in the Philippines—is it difficult when you go to these places to make movies in your style?

BL: A little bit difficult. But I'm so lucky, you know, because Dick Randall, [more than] anybody, they have given me more chance to do myself. So it’s better.

WS: What did you learn from being at Shaw Brothers?

BL: Nothing! So I left! Same as Bruce Lee before—he shot movies with Golden Harvest: The Big Boss [1971] and Fist of Fury [1972]. He said, “Fuck no—I go to make Way of the Dragon [1972].”

David Gregory: You learned how to fight onscreen, though. Because at Shaw Brothers, didn’t you hurt your opponent at the beginning?

BL: Oh yeah. At that time, I didn't know… I never made movies before. I’m studying, you know. So one day… I shoot five or six days, only comedy, okay? So I'm not enjoying it, but one day the martial arts director said, “Okay, tomorrow you need to fight, or somebody else [will do it].” So I'm very happy. I exercise and I want to shoot. When I started the shoot, because suddenly, you know, “Camera!” But one of the guys wanted to cheat me, you know? I don't know… I forget already, I think it’s just real fighting… I hit them, and another guy is “Pow!” again in my stomach… two guys go down. The director: “Cut! Cut! Cut!” I say, “What happened? What happened?” He said, “They cannot move—one guy, because his bone is breaking.”

This is good for my idea. Why? We go to the hospital and I know his bone is breaking, so I put this in my movie. I hit somebody—immediately. You can see blue light… [Le is here referring to a scene in his 1982 directorial effort Ninja Strikes Back in which, after hitting an opponent, the screen cuts to animated x-ray footage of the opponent’s bones breaking. This would become something of a signature visual motif in Le’s films.] Just gives me idea. So before we go to the hospital, you know, it's real. And [the next day], the newspaper in Hong Kong, China, you know, “Bruce hit somebody…” [Laughter]

From Enter the Dragon, the big villain, Shih Kien, he’s very smart. He told me—because he knows after two or three days, maybe I fight with him again! And he comes to tell me, “Making, moving, and real fighting—that's different, okay? You cannot use your whole power to hit me. You know? You cannot do that. I don't want to break. You and me.” He is also the master, you know? He's really my master. I'm 20 years old, and he’s already 65, something like that, you know. “Don’t actually hit me—just touch me! We have special effects, it’s very good-looking.”

WS: You worked with another villain from Enter the Dragon, Bolo Yeung, on many films. What do you remember about him?

BL: He's a good fighter. Good action. A good fighter. But because he believed in me… You know, because I made the movie, he fights with a bull. [Note: This memorable moment—not even the only bullfight scene in a Bruce Le film—occurs in 1979’s Bruce the Super Hero.] But you know, he didn’t want to hit it. I'm also here as an actor, and I'm director, I'm producer… The money is very important! [Laughter] So I don't want to use the time! So I told him, “Okay, don't worry about that. I take the bull.” I asked the doctor to come inject the bull [with sedative]. But after one hour, the bull is still kind of strong and energetic even after the injection. An hour afterwards! I was so angry because we are on budget—we cannot do that. I spoke to the doctor: “How can I do it?” “No, I injected it already.”

Once the bull falls down, it won't get up. So you have to kind of think about that, knowing that once the bull is laying on the ground, it’s not going to come back up. But I must show him, because otherwise, because I'm the producer and director, you know, I don't want to spend the time, you know, the money is very important. Filmmaking is just make-believe.

JD: When you started directing action scenes for your movies, how would you decide that the action scene is long enough? How would you approach putting an action scene together for your movies?

BL: There’s a rhythm and pacing to it. So for example, in Goldfinger, when you have Oddjob throwing the hat, you immediately know he's a bad guy. So you look forward to him finally fighting James Bond, but they kept it until the very end in the Fort Knox sequence. So pacing is very important, and also to give the audience anticipation of the villain, when the villain faces the hero.

JD: Because in Enter the Game of Death, that’s 80% action. Was that a decision on your part, that there should be that many action scenes in the movie?

BL: Audiences want to just see action. I go to many theaters, I go to many buyers, like Dick Randall or somebody, we sit down, we watch the movie. When you fight, they’re very happy. When you [do a] love story… [Snores]. And then, I want to see the movie. I put a cup, come wake up, wake up. Fight again. That's all. In martial arts [movies], they don’t need to talk about fights. Jackie Chan movie: fight at beginning, fight at the end. Anybody like it?

WS: With your style of fighting onscreen, there are elements that are similar to Bruce Lee’s style, but it’s quite different in a lot of ways. Could you talk about what you got from him, but also how you changed it to suit yourself?

BL: At that time, they had directors like Lo Wei who worked with Bruce Lee. So when Bruce Lee passed away and then they wanted to make movies with me, obviously they wanted me to, you know, fight in the style of Bruce Lee. So after I made about ten movies like Big Boss Part II, I decided to start changing. So my style, the difference in the style is almost like I'm trying to do what Bruce Lee would have done if he was still alive, but that because he passed away earlier, he couldn't do it. So mine, the style that I'm trying to develop would be something that will be in a way that hopefully Bruce Lee would have done the same had he been still alive.

JD: How did you meet and start working with producer Dick Randall?

BL: In 1970, something like that, I started my movie [career] in Shaw Brothers. After that, I made two or three movies, and he bought the movies. I didn't know him. But one day, he brings one director to come to Hong Kong. You know, this guy wants to make the “Jungle Blue Lee”…

Michael Worth: King of Kung Fu [1976].

BL: At that time we met and he said, “Bruce, I buy all your movies before—what do you think about that?” He’s a very nice guy. Okay, he buys movies and we work together, and after that I changed my mind. In 1980, I started [directing]. “I want to shoot in Italy, can you give me a chance?” “Okay, no problem. You come.” I shoot in Italia; I shoot in Paris. In Paris, one of the producers is Andre Koh. Andrew Koh, he’s the French producer because he buys The Big Boss Part II. He made money. Part II, he made money. And he liked me because he said, “Bruce, can you give me the rights for France?” And we both put together the production of this movie. So we’re beginning, and then here we have a very good time together. He came to the Philippines, he came to Hong Kong, he wanted to buy some kung fu movies or ask me to buy. You know, even Bruce Li movies, he likes to buy, and I could ask for Jackie Chan movies also, I talk to somebody at the movie to do it.

WS: What do you remember about working with the Cameroonian action star Alphonse Benni?

BL: Cameroon Connection [1985], yeah. This guy Benni, he's not the producer. No, he's not the actor. He only buys [for] the market in French. I know that because he always comes to talk with me, “Bruce…”—every day. I'm not interested because he's the buyer, in my opinion. But one day, my friend told me, “Bruce, Benni wants to shoot one movie in Cameroon. Are you interested in going there, to shoot together?” But at that time, I wanted to find something new. Something new, you know. I had already shot the bull in Spain. I want to shoot not in Cameron, but Kenya, because I see many panthers… you know, I want to fight with the panther! [Laughter] I fight with a tiger before. Fight with the panther. I fight the animal. I want to think of something different, you know? So I go there.

But he has small budgets, so…

MW: No panther.

BL: No panther. [Laughter] So I forget about it; what I do now, I do for him, you know? He wants to be an actor because he would like a script for him. And I don't know the script, I don't know anything, but I just want to find out my new way. I always find my new way.

WS: I mean, you, as somebody who acted and worked on so many movies before that… Was he easy to work with in that way?

BL: It’s okay. You know, he liked me very much. So I go there, very easy, you know? But you know, Africa is very poor. When it was the first time I arrived in Africa, you know, it was like many, many friends. I was very afraid. I worry about what [will] happen, you know? I put my camera in my back… I worry they’ll steal my camera! I go to the theater, you know, all the people that watch the kung-fu movies shout, “Ohhhh!!!!” I stood in the back, I look at people.

But small budget—very, very small budget, you know. We don't have money, no negative—anything, they don't have it, you know? But I have to do this new market, African market, [because] maybe they like it. I shoot in Italy, Italian people like it; I shoot in Africa, they like it, we find the market. Same as Bruce Lee also: he makes The Big Boss and Fist of Fury—he finds another way. He goes to Italy to make Way of the Dragon, finds a big market. Enter the Dragon, find a big market. This I started to learn.

JD: Did you ever find it difficult with fighters on screen, especially ones that weren't trained for fighting onscreen? I think of someone like Bill Louie [a locally famous New York-based martial artist] in Bruce vs. Bill [1981].

BL: Of course it’s difficult. But you have to overcome. They don't know film fighting and they're trying to showcase the real wuxia on screen, but it’s their only opportunity, so they almost always try to make them look better than myself. So I have to try to challenge them and overcome them. If I don't overcome them, they won’t follow me. So when I was making Bruce Strikes Back 1982, you have the guy with the Okinawa size, and he punched through my hand…

[Bruce shows the room a still-visible scar on his palm, to much ooh-ing and aww-ing from the interviewers]

BL: He goes, “Ohhh Bruce!” I said, “We’re shooting! Don’t stop!” After I finish, I just said, “Anybody come? No, no problem…” That's why that way he knows that I'm not afraid of him, that I can actually just beat you, kick your ass. Because if I've done like, “Oh, my God, that hurts!” then obviously he's kind of won. So afterward, for the next fight scene, they kind of just follow what I have already kind of conquered them, conquer the conflict. When I'm fighting the bull, it's like, if the bull chases you, you know, your instinct is to run. But if you stop, you maybe die.

So I fight with Bill. This guy started from the beginning, but the producer wants to let him be a star. He comes to Hong Kong to shoot with me, but I give him many chances. I said, “You do it.” I told him honestly one day in Taiwan, one day in mid-drink. I said: “Tomorrow… I kill you.” [Laughter] “I told you, no joking. Okay? Anyway, fuck off.” Because he always like this… [imitates Bill Louie] but he don't know. You know, five or six times karate [champion], he thinks he's the big fighter.

But I respect him. I would show him my stances and moves and now he knew it because I was actually kind of pissed at him. The producer brought Bill over because the producer wants to build him to make money in action. Okay, I’ll give him a chance—but don’t treat me like a fool. But I’ll give you a chance, I’ll give you [a chance] to be an actor, like Benni also. I give you [a chance] to be a star. But one thing [is] very important: you must believe me, I’ll do the best in the movie.

WS: Working in the Philippines, what was that like? Because those films were obviously very low-budget. What were the obstacles there?

BL: In Philippines, small budgets, but we try to make the best. So [it was] very difficult to find some good actors, you know? We find the gym, we find some workers, you know, who are fighters.? But the budget is not big. And the time in the 1970s, we make many kung fu movies, [in which] we also don't have a big budget—small budget [in] between.

JD: I would love to know, you directed a movie called Comfort Women, and then you made a remake of it, The Eyes of Dawn.

BL: You see the movie?

JD: We’ve seen Comfort Women, not the newer one yet. How did you come to that project?

BL: In 1991, in Korea, at that time they wanted to make a TV serial, Comfort Women. They want to come to China. But at that time, there is no diplomatic relations between Korea and China. Korea wouldn't let the Korean director make that film. The Korean director, very big television [director], one of the best directors in Korea. And then they find me to make this movie; brought me to Hong Kong and then to China and we were able to finish that project about comfort women.

And then, the picture: very big in Korea. It won a lot of awards. And then, I make the comfort women movie again.

WS: The Eyes of Dawn.

BL: I wanted to. So I spent ten years around these comfort women and some of the Chinese heroes. I [research] this history about the movie. Now, [I’m spending] a lot of money for myself to make a TV serial for the comfort women. So, I’ve come to America because I want to find some location for the leading lady. Was she going to China to find out about the Second World War story?

So that's a different [project]. And I really want to make kung fu movies—but I don't have time. So David [Gregory] and them came to China, to Hong Kong—they want me to do it, so I don't have much time. And then, I don't want to do like this one, because why? Kung fu movie already finished. If you have something new, you must have something new, something different. So one day I [talked to] David: “Oh, that's a good idea. Really good idea.” So last year they called me: “Okay, okay, we do it. Come on.”

Frank Djeng: What he’s saying is, he kept delaying letting us interview him for our documentary. So, you know, like six years after we first approached him, he finally felt that now's the time. So he accepted David’s invite for the interview, and to him, this was perfect timing. This is the right time for the opportunity to kind of get this kung-fu movement revival going again.

Enter the Clones of Bruce played across the country last month. Severin will release a 14-film Blu-Ray collection, “The Game of Clones: Bruceploitation Collection Vol. 1,” in June.