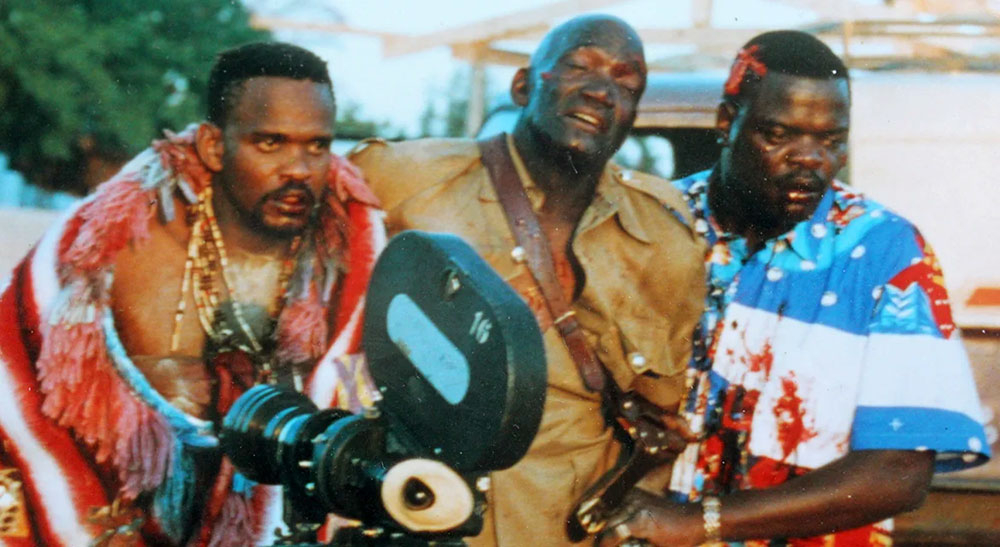

The word visionary gets thrown around a lot these days, but there’s simply no other way to describe the Cameroonian filmmaker Jean-Pierre Bekolo, who is arguably most famous for his feminist sex worker vampire satire Les Saignantes (translated alternately as The Bloodlettes or Those Who Bleed, pictured at top) from 2005. This month, New York’s French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) has been showing “African Futurism: The World of Jean-Pierre Bekolo,” a selection of Bekolo’s work which continues tonight with his breathtaking black-and-white science fiction film Naked Reality (2016)—set in an Africa 150 years into the future, entirely urbanized and devoid of individual national boundaries. The series will conclude with the U.S. premiere of Bekolo’s new “fake ethnography” We Black People, about African enclaves in the Chocó Department of Colombia.

As both a filmmaker and a theorist, Bekolo is a relentlessly inventive thinker, so it’s especially good news that the FIAF screenings are the kickoff for a nationwide tour which will encompass Rochester, Harvard, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and more—hopefully keeping cinephilic attention on this utterly sui generis film artist. (Never one for mystique, Bekolo has also made the films available to stream at very reasonable rates on his VHX page.) Bekolo zoom-ed in from Cameroon for a long-ranging discussion of his career, his filmmaking technique, and his evolution as a critic of what he calls calabash cinema—selling outdated images of a remote, mythical and simplified African continent to Western audiences one film festival at a time. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Steve Macfarlane: I wanted to call this tour unprecedented, but the truth is you went on tour over 30 years ago with your feature debut, Quartier Mozart [1992].

Jean-Pierre Bekolo: Floyd Webb invited me to the Chicago Film Festival. I think that was the same year as the first New York African Film Festival as well. I did not travel to many of [the screenings], but in the end Quartier Mozart was brought to around three hundred universities in America. It was huge. California Newsreel was distributing the film and at that time I think people were hungry for new material, [for] a new way to talk about Africa. And my second feature Aristotle’s Plot [1996] was the first African film at Sundance.

SM: When I first saw Quartier Mozart I wondered if the plotline—about a girl who is transformed by a witch into a man in order to better understand men—drew from a specific tribal legend or story. This is an unfortunate tendency, to assume everything is tribal, ethnic, or ethnographic...

JB: I was 25 years-old. I was not very in tune with African cinema. To be honest, I didn’t even like the canonical films too much at that time, but I learned to like them as I grew up. Cameroon has like 250 ethnic groups, so there’s obviously no way to make a film that will speak for all of them. But the film is in Cameroonian French, which is a kind of syncretic language that results from colonialism, in urban areas. What I wanted to show was the daily lives of young people in the city of Yaoundé. Even if I added a mystical dimension—the guy who makes genitals disappear with one handshake—I was more influenced by urban myths than ethnic or tribal [ones].

SM: Your follow-up film, Aristotle’s Plot, features gangsters who have built their identities around Western entertainment and movies and a conflict that erupts when a young cinephile wants to roll the clock back and show African cinema.

JB: Djibril Diop Mambéty was just 27 at Cannes with Touki Bouki [1973]. When I met him, he was an old man who could only make short films. I was really sad about that kind of destiny, or non-destiny, for a filmmaker as talented as Djibril. I feel like African filmmakers are always young-and-upcoming, or they’ve somehow become elders, fathers, ancestors. In relation to Africa and the West, there’s a paternalistic idea that if you’re young it’s okay [and] if you’re old it’s okay, but if you’re mature, or are maturing, festivals have no interest in you.

Today, there’s also a lot of what we call calabash cinema—nobody in Africa is drinking from a calabash nowadays! It’s a means of showing the West what it wants to see: an Africa that doesn’t exist. Africans are supposed to be real and you get into a situation where the imaginary becomes the luxury of the bourgeois. It’s for the West, not for us, and we’re not supposed to compete with the West. Now you can see why I never have big budgets. [Laughs]

I wrote an open letter to the Berlinale film festival a few years ago called “Don’t Talk About Us” basically saying, “Why don’t you want African cinema to talk about us and our relations? Why don’t you want films where Africans talk to each other?”

SM: Sometimes I wonder if the 1990s weren’t a better time for Black filmmakers to get access to the kinds of budgets we’ve been discussing. Maybe it’s an exclusively American phenomenon. I’d love to get your read on this.

JB: A lot of people got excited about my work due to that trend—[Melvin] Van Peebles, Spike [Lee], Charles Burnett, many others… There was a lot of hope in the 1990s. Spike had the studios backing him, listening to him. But the cinema of the 1990s was interesting unto itself beyond Black cinema, and for me those are still my cinema references. I have not been able to fabricate the same excitement more recently. I haven’t found that hope again.

In France, someone like Idrissa Ouédraogo was getting the same budgets as French filmmakers, the same distribution, the same exposure. But starting in the year 2000, the budgets were split up—Francophone African budgets were ghettoized. The whole idea of African cinema competing with the rest of the world kind of disappeared. Now it’s become more tokenized, Africans have become more tokenized. For me, it’s no longer about quality, it’s that festivals don’t want to be labeled racist. It’s different from the 1990s, when it really felt like at least cinema was at stake.

SM: Can you say more? You’re describing a kind of drift in priorities.

JB: I was still a student when Do The Right Thing [1989] did not get the Palme D’or in Cannes. I remember Spike Lee was angry and saying bad things about Wim Wenders, about Cannes. But the people didn’t care about the Palme, Spike had already made a breakthrough. It was a great moment for us, as student filmmakers.

The debate was ugly, but these kinds of debates do not even happen anymore because there’s a lot of political correctness—this is just my feeling. The debate has switched from the aesthetic—questions about cinema—to the political. Back then, I was too idealistic, too naïve. But today I am really having a hard time. It’s not about cinema anymore. You can tell when you look at the films. There’s no risk taken in the style. I remember seeing She’s Gotta Have It [1986] and really dreaming to do with cinema what jazz does for music—a little bit of improv, something unpredictable, you know?

Today the pressure is on Africans to pretend that they are professionals making clean professional films. To be honest, I don’t have that pressure. I can’t be apologetic about being broke. Being poor is not a problem, but lacking something to convey in a cinematic way—this is a different poverty.

SM: Well, in American independent cinema, or what exists of it today, the fetish is industrial—this kind of fake-it-til-you-make-it attitude where your mode of production must cosplay that of a big commercial production. At some point, you begin to worry whether directors are spending more time in meetings than making their films.

JB: I read an interview where Djibril said he would never be a professional. “Once you become a professional, the art is gone.” I’m paraphrasing. I actually like the fact that with artificial intelligence—where are the filmmakers? Maybe it’s going to help because I feel like creativity needs support. You rely on so-called professionalism. How are you going to do a car chase when no car has petrol? Not even the police car. There are situations where, if you look at the reality of Africa, you’ll realize there’s no way this car is going to get you three miles anywhere. This is where the filmmaker steps in, as an intermediary.

SM: From an outside perspective, the jump from Quartier Mozart to Aristotle’s Plot appears meteoric.

JB: I went to L.A. One of the executives tried to meet with me and he was very honest: “I just met with you because I didn’t know Africans were making films and I wanted to meet one of them.” [Laughs]. Another experience: At the London Film Festival I was with [Quentin] Tarantino in a special competition for first-time filmmakers. Tarantino [was there] with Reservoir Dogs, I was there with Quartier Mozart, and Julio Medem with Vacas [1992]. We met at a bar and I remember Tarantino came back with a bunch of books he had bought—French cinema books translated into English. He was preparing Pulp Fiction [1994].

In Cameroon, not much was happening as far as cinema was concerned so my base became Paris. I started realizing that because I’m from Cameroon, I would never have the same destiny as Tarantino. Being from Africa, I couldn’t see much of a future in the business of cinema, if that makes sense. And I had actually made three films in four years: Quartier Mozart and Aristotle’s Plot, but also a film I developed in Memphis at the invitation of Jacquie Jones, editor and publisher of the Black Film Review. The first title was Coming from Africa, later renamed Have You Seen Franklin Roosevelt? [1994] It was about an African named Molah Franklin Roosevelt who is shipped to America in a FedEx box. The point was that African-Americans did not possess the same confidence that he did. I think I have a very poor quality copy somewhere.

Anyway, I had been going to film festivals but I didn’t actually have much to talk about. Three films back to back to back… At some point I began to feel like I didn’t know anything about life. I had also become too business-minded so I started traveling. That’s the time I went to Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia—I was invited by their theater department. Then, I went to UNC Chapel Hill. Then, to Duke University, where I began preparing Les Saignantes.

SM: Duke is where you developed Saignantes, your biggest film.

JB: But since I was coming off of Aristotle’s Plot I didn’t get the financial support I was anticipating. I had to go off of a grant I had received. Not having anyone tell me what to do was like Christmas.

From 2005 to 2009, I was busy with that one film. Touring, but I also mean busy as in I was exhausted. My mother had passed away. I was in the editing room for a full year by myself. I also did it because I love editing and I didn’t want anybody to touch my film. Someone needed to kick me out of that room, but only if they had the strength to do it. That’s what’s great about making films—the moment when everybody is doing what he loves. As an editor, it was great to be able to do things instead of talking about them. Everything else in filmmaking is so verbal. I was trying to push the film to the limits—a trance object, a film that’s like voodoo.

SM: You decided to open Les Saignantes in Cameroon, right?

JB: I opened it there first. My mother passed away when I went to open it, at the exact time of the release. We had to tour the whole thing, it was difficult. But the reception was amazing. People had never seen a cinema like this. I would say, when the movie came out, people were blown away. It was important to show it there. We got censored at first—the committee said the film was pornographic and against the regime. I fought back. I had to explain a few things to the committee and they agreed [to show the film] so long as I put a sign at the beginning of the film and made a few little changes. I agreed, but I didn’t change the film.

SM: Is it safe to say Les Saignantes was your biggest film?

JB: Films are like people: some are rich, some are poor. If you aim for the kind of high production values we were discussing before, there’s a chance you will never make another film afterward, even if you get them. You’ll be looking for funding for 20 years. If nobody gives you money, that means nobody is expecting a return on their investment. Le President [2013] was made for two thousand dollars. I made a film about the president to ask: Are films important? Are filmmakers important? We under-estimate, you know? Le President was banned. That showed me the power of cinema. I was satisfied by this outcome because I was able to relate something about Cameroon.

SM: Were you ever in danger?

JB: I know I was followed, at some point, by some people… A lot of people were scared for me, but to be honest, I didn’t think anything would happen. I was maybe too naïve, that’s all I can say.

SM: Well, sometimes the only reason a thing can happen is someone’s naïveté.

JB: You don’t always know when you are in danger.

SM: Tonight FIAF is showing your Brechtian sci-fi parable Naked Reality. IMDB says the budget was 100 euro.

JB: Whenever somebody gives you money—it doesn’t matter how much it is—it’s a very strong statement. Somebody wants to support my work, they don’t care what I do. The idea for Naked Reality was to make the entire movie in a studio. At first it was to be green-screened, but then I started thinking of the effects I would [use]. The studio itself was already a kind of surreal world and I thought I’d use it as a set for the film. In Africa, when you go to a rural area, the kitchen is not in the back. The kitchen is somewhere in the middle of the compound, so the cooking is not hidden. In many cultures people just bring food from somewhere. I was thinking: What if we did it the African way, where the cooking and the eating happen in the same space so that the film and the making of the film are all together? That’s why I called it Naked Reality. Maybe even the filmmaking practice should be naked.

The whole concept of the film was [inspired by] African religion—the question of the world you don’t see. It’s the early days of cinema and for me, those special effects are really something that help tell the story. I felt like all these things were possible—going back to theater, going back to old cinema techniques. Unfortunately, the industry and the whole system is pushing us toward one gamut of tools.

SM: It seems obvious but nevertheless it must be said, in most cases the gamut of tools is not liberating people’s imaginations.

JB: People don’t look at technique, they look at trends. 2024—all the technology we have, we wanna talk about budgets? It’s silly. I went to see a big film this summer, what was it…?

SM: Oppenheimer? Barbie? Mission: Impossible…?

JB: I watched all of them. I’m very disappointed. It’s always nice to watch a movie. Of course, I can’t deny that fact. But at the same time, I wasn’t impressed. This is what young aspiring filmmakers are trying to catch up with? Third-world filmmakers are dreaming of this? This feeling of we are making progress, we are catching up—for Africans it’s always this idea of catching up. It’s bullshit. People live where they are with what they have. Catching up to what? There’s not enough freedom in the minds of these filmmakers.

SM: I’ve read about Netflix making huge investments in African markets.

JB: It’s very simple what Netflix is doing. It’s obviously a penetration of the market, which is great for filmmakers who want to have access to those audiences. The excitement around Netflix coming to Colombia, well… I was disappointed when it turned out to be about Narcos [2015].

When you watch a movie on Netflix you’re not watching a Jean-Pierre Bekolo movie. You’re watching Netflix—anyone trying to have a cinematographic style will disappear. Obviously, the great filmmakers like Scorsese are making Netflix films. But for me, it’s about expressing myself. For my self-expression to become Netflix, for me it would be a problem.

Netflix aside, Nigeria is very interesting because there’s the Nollywood idea. Do you remember the girls who were kidnapped in 2014? 276 girls were taken away by Boko Haram fighters. We’re talking about a country that produces, what, a thousand movies a year?

SM: Google says 2,500 films per year.

JB: 2,500 films and not one could see this coming. Not one of the movies could anticipate a phenomenon like Boko Haram. Not one of them could actually say something about the place.

What is cinema doing when it cannot show what is going on? You’ve seen my films, you know I’m not interested in realism—I’m just talking about people expressing themselves. It’s about a kind of vision of where the country’s going, an anticipation, or where we are in our relationships. There’s an expression: “You will look left when somebody is robbing you to the right.”

SM: Tell me about the last film in your FIAF cycle, We Black People [2021], which you shot in Colombia.

JB: I didn’t actually go to Colombia to make a movie. I went to a workshop in Bogota and when I was leaving, a Black girl came to me at the airport and said: “Did you see Black people?” I was like, “Well, I saw them on the street, but no…” She said, “You came to Colombia and didn’t see Black people?” I was like, “I’m sorry, I did what I had to do, uhh…”

She made me feel so bad that I promised to her I would come back and meet Black Colombians. A few months later, there was a project called Black Atlantic—done by the Goethe Institut—calling for a program between Latin America and the Afro-American diaspora. They called me and said, “We see that you’ve been to Colombia, are you interested in this? It’s not a film project, it’s a counter-cultural project, an experiment.” It was Christmastime. I remember they sent me the budget and I decided to spend Christmas in Bogota. Then, I went to Cali. “Go to Chocó,” everybody told me. Chocó is like the town of Douala, in Cameroon. On January 2nd, I bought my ticket to Chocó, to discover this African community in the middle of nowhere.

I can say what I have learned in one word: Entanglement. I couldn’t understand why people who left Africa 500 years ago, ten thousand miles away, were behaving the same all these years later. How is Africa influencing these people who left, or who were taken away 500 years ago, on a daily basis? I started making the film but I hadn’t planned to make it. My feeling was really that maybe there are more Africans than us. Maybe that little bit of Africa in Colombia will tell us what Africa is really about: What they eat, how they braid their hair—for them, it’s resistance.

Naked Reality screens tonight, February 20, at FIAF as part of the retrospective “African Futurism: The World of Jean-Pierre Bekolo.”