It has become a habit for leftists to ask one another, “How were you radicalized?” Of course, it’s through learning each other’s histories that we can arrive at better strategies for revolutionary change, but this particular question has become something of a piety, the stories taking on the genre of the Christian conversion narrative. In reality, the experience of radicalization can be a lot less straightforward. People’s messy, uncertain journeys into political action are a uniting theme across the filmography of the director-and-producer husband-and-wife team of Kazuo Hara and Sachiko Kobayashi. Over fifty years, they’ve produced seven documentaries and one narrative film, all of them available through Japan Society’s “Cinema as Struggle: The Films of Kazuo Hara & Sachiko Kobayashi” retrospective. Their films, few of them well-known outside Japan, are incredible documents of struggle, change, and political awakening.

Their first film, Goodbye CP (1972), follows men with cerebral palsy organizing, pamphleting, and fundraising as part of an activist group that advocates for people with the condition. We follow these men’s lives on the edges of Tokyo society, often in intense poverty and difficulty. Unlike most films about disability, there is no attempt to turn the suffering caused by an ableist society’s disregard into something ennobling, educational, or beautiful, but they are not simply victims either, as they often interact with and resist the film crew and its directions. Hara and Kobayashi don’t gloss over their subjects’ suffering or their flaws. At one point, when a subject’s wife starts screaming that she’ll leave her husband if he doesn’t stop participating in the documentary, it feels like the film’s intimacy crosses some important boundaries.

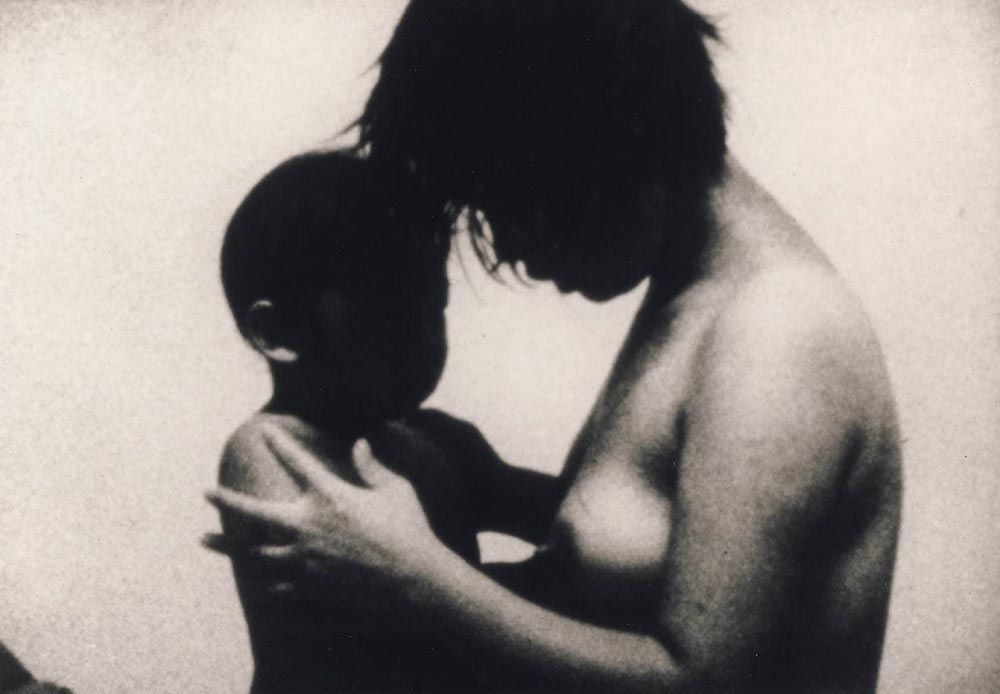

Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 (1974, pictured above) was, by Hara’s own admission, conceived as a way for him to keep his ex, Miyuki, in his life. They have a child together, but in 1972 Miyuki chooses to move to Okinawa (an island known since 1945 mostly for its US military base) with their son. When Hara arrives in Okinawa, Miyuki is living with another woman, and they are in an intense but physically unconsummated love affair. We see Miyuki berating her partner for her internalized homophobia and her refusal to sleep with her. It becomes clear, as Hara admits, that their ongoing conflict is caused by the film crew’s presence. A little later, Kobayashi, now Hara’s girlfriend and pregnant with their first child, shows up on camera, interviewing Miyuki. We see Miyuki berate and insult Hara and Kobayashi, as Kobayashi holds a microphone and tries to stand her ground.

Then Extreme Private Eros takes a turn. We follow Miyuki’s brief affair and pregnancy with a black GI and her single-minded mission to have the baby completely alone. The birth, taking place in Hara’s Tokyo apartment, is filmed live, and Hara, so overwhelmed by the sight, doesn’t realize that his camera is out of focus for the entire ten-minute take. We then see Miyuki becoming more and more involved in organizing health support for sex workers in Okinawa. At the film’s climax, Miyuki decides to leave Okinawa for Tokyo and writes a pamphlet about her experiences in the island’s sex work milieu. But she and Hara are stopped by a group of gangsters — presumably the managers of the sex trade — who destroy the pamphlets and beat up Hara.

This turn from the personal to the political through violence is nowhere more embodied than in Hara and Kobayashi’s most famous film, The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987). It follows 62-year-old Okuzaki Kenzo, a survivor of Japan’s particularly horrific military campaign at the end of World War II in New Guinea that devolved into starvation and cannibalism when totally surrounded and isolated Japanese soldiers were not allowed to surrender. After returning to Japan, Kenzo devoted his life to, as he says, “fighting the Establishment,” spending 13 years in solitary confinement for killing a real estate developer, firing a slingshot at emperor Hirohito, and distributing obscene pamphlets of the emperor.

We see Kenzo confronting, questioning, and even physically fighting the officers involved in the murder and cover up of two soldiers. These old war criminals are almost as shocked as we are to discover that Kenzo is willing to judo-throw them to the ground to get to the truth. He is perhaps the most fearless man ever captured on screen, like some mad angel of justice and revenge, refusing to forget or stop fighting for the dead. Naked Army is well worth the price of festival admission on its own. It is also, unjustly, the only film in the series that has anything like an international following.

A Dedicated Life (1994), a documentary about famous novelist Mitsuharu Inoue, marks a definitive change in Hara and Kobayashi’s style. The film, still focused on a single iconoclastic figure but a more famous one (Inoue was a one-time Communist Party militant and major figure in left wing literature), feels more like a traditional documentary. It is their first film that features non-diegetic music, mostly synced sound, and a more traditional narrative structure.

After The Many Faces of Chika (2005) it would be a dozen years before their next film, Sennan Asbestos Disaster (2017), but two more films followed in quick succession: Reiwa Uprising (2019) and last year’s Minamata Mandala (2020). As their early films traced the journey from the personal to the political, they gradually shifted their focus from the politicized individual to collectives of resistance. And as their films’ scopes grew, so too did their runtimes (at 3.5 hours, Sennan Asbestos Disaster is among the shortest).

Sennan Asbestos Disaster follows workers in Osaka, exposed for years to toxic fumes from asbestos factories, as they maintain a nearly decade-long legal and political fight for restitution. The film’s length allows each of the plaintiffs and activists to become protagonists in their own struggle and to create space for grief and mourning for the victims. Once again the filmmakers resist easy romanticization or heroism, instead showing the weaknesses in the activists’ internal dynamics and social attitudes. It is hard not to see this documentary, though filming began in 2008, as being in dialogue with the environmental and health movements following the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011.

Minimata Mandala (2020) is a truly epic achievement of film as historiography and activism. Filmed over 15 years, it opens on a significant but largely symbolic 2004 Supreme Court victory for people suffering from Minimata Disease, a neurological condition caused by extreme mercury poisoning that drastically affects cognition. The Chisso corporation, from 1932 to 1968, pumped industrial mercury wastewater directly into the ocean, and people in and around the plant in Kumamoto Prefecture began developing mysterious symptoms.

The issue has been a national scandal in Japan for decades. In 1977, the government based the criteria for diagnosis (and therefore, for government support) on such bad science that more than 80% of sufferers were denied coverage and called “fake patients.” Then, in 1995, Shisso and the government made a “political settlement” of ¥2.1 million per patient (about $300,000), but if patients agreed to the settlement they had to drop all lawsuits.

By 2004, when the Supreme Court officially apologized for the 1977 criteria, even the youngest sufferers of Minamata were in their mid to late 30s. Their entire lives have been defined by both neurological disability and malicious government disregard. We watch as these people and their scientific and legal allies continue to fight for recognition, diagnosis, and reparation. The government’s repeated “sincere” apologies are shown to be craven, self-serving gestures.

Over the course of their careers, Hara and Kobayashi’s early guerrilla-style filmmaking, with its anarchic combativeness, slowly gave way to a more conventional documentary aesthetic, with talking heads interviews intercut with archival footage. But while their style has changed, their insistence on giving space to their subjects and involving them in the process of filmmaking has not.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to ravage the globe, the forms of resistance to government and corporate malfeasance pictured in both this film and Sennan Asbestos Disaster offer a valuable window into fights to come. The films of Hara and Kobayashi are not simply stirring documentaries in their own right but valuable historical documents about the long durations of political struggle and social movement.