Back when I was an eleven-year-old burgeoning anime fan with limited access to a computer, I was obsessed with Cartoon Network’s Toonami programming block. My afternoons were filled with back-to-back episodes of heavy hitters like Sailor Moon and Gundam Wing mixed with less popular, but in my mind “grittier,” more mature space operas like Outlaw Star. It was on one of these afternoons that I saw a commercial featuring two people in space helmets, introducing themselves as Daft Punk and plugging their animated music videos that would play in Toonami’s less-censored, late-night block Midnight Run. The teaser clip showed beautiful blue-skinned, blonde-haired people with jeweled headbands playing in a band, alternating romantic close-ups of their detailed features with the pulsating beat of a kick pedal hitting a drum. The style of anime had a different quality from what I was used to seeing at that time, a look and vibe that somehow read as more retro and thus, to me, automatically cooler; a must-see for a nerdy kid actively attempting to develop a more acquired taste

The four videos Toonami featured, for Daft Punk’s tracks “One More Time,” “Aerodynamic,” “Digital Love,” and “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger” (all classics), were part of their 70-minute anime space opera Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem. In the dialogue-free film, a band of extra-terrestrial musicians are in the middle of playing a packed show when they are kidnapped by an evil record producer. He brainwashes them, erasing their memories and their skin color, and repackages them as a human band called The Crescendolls. As they are granted fame and fortune, the band discovers the dark plans and fights to return home, reclaim their identities and control over their art. In the end, we reach a classic realization: it was all a dream, the result of a young boy listening to the Discovery album while playing with the action figures in his room and imagining galactic adventures.

—

Last week, the French electronic duo, Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter, announced they were disbanding, ending a 28-year-long career as Daft Punk. And perhaps appropriately, they did so with a film: an eight-minute long segment from their 2006 film Electroma, entitled “Epilogue”. Two robots, clad in leather jackets with the band’s logo on the back take a golden hour stroll in the desert and decide to part ways. One punches into a keypad on the other’s back, activating a countdown timer, and watches him explode from afar. The remaining robot keeps walking in the direction of the sunset. It’s a moody, silly, and oddly poignant send-off for a band that, while attempting to go over-the-top, never seemed to take themselves too seriously. This playfulness, however, doesn’t mean they had nothing to say. Mixing Chicago house, techno, and ‘70s disco, Daft Punk’s musical models were always front-and-center. But the band’s incorporation of their eclectic film/animation influences into the visual component of their project (including their own forays into the directorial space) was equally significant in their creation of a sentimental speculative fiction.

From what I’ve gleaned, Homem-Christo and Bangalter’s adolescence looked rather similar to mine. The two allegedly bonded over having grown up watching imported Japanese animation (which was rather popular on French television during the ‘70s and ‘80s) and hunting down cult films and obscure music. While they were recording 2001’s Discovery and began to imagine what a companion film could look like, the evocative pull of vintage anime emerged as an appropriate fit. They went to Japan and courted their childhood hero Leiji Matsumoto to visually supervise the project. Matsumoto is known for his dreamy space operas like Space Battleship Yamato, Galaxy Express 999, and the classic series Space Pirate Captain Harlock, which Homem-Christo and Bangalter cite as their favorite anime. His galactic worlds, while envisioning a future in space, are also steeped in the images of fairy tales: pirates with capes and maidens with long hair and almost equally long eyelashes adventuring on heroic quests. This romantic vision of a future tinged with aesthetics of the past courses through Daft Punk’s work, the space opera itself running counter to more cyberpunk, dystopian envisionings of an advanced technological future.

Daft Punk’s visuals have been shaped by film from the start. Their earliest videos were directed by (at the time) up-and-coming filmmakers such as Spike Jonze (“Da Funk,” 1996) and Michel Gondry (“Around the World,” 1997), two artists who would go on to explore the emotional, human side of technology in their work. And while they scored a big-budget nostalgia cash-grab like Tron: Legacy, also making a cameo appearance in the movie, Bangalter has also collaborated on several scores with Gaspar Noé (Irréversible and Climax). The duo began to step behind the camera themselves for their own music videos before working on their feature film Electroma (2006). An ode to all their film forebears, from Gus Van Sant and David Lynch to the vast desert expanses of ‘70s road movies and Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970), the dialogue-free movie follows two robots (credited as “Hero Robot #1 and “Hero Robot #2”) as they traverse the Southwestern American landscape in the search to become human. It’s a pastiche of film fandom in the same way that their music is a bricolage of their youthful influences. Electroma received mixed reviews but accomplished what the pair probably wanted from it all along: becoming a midnight movie mainstay.

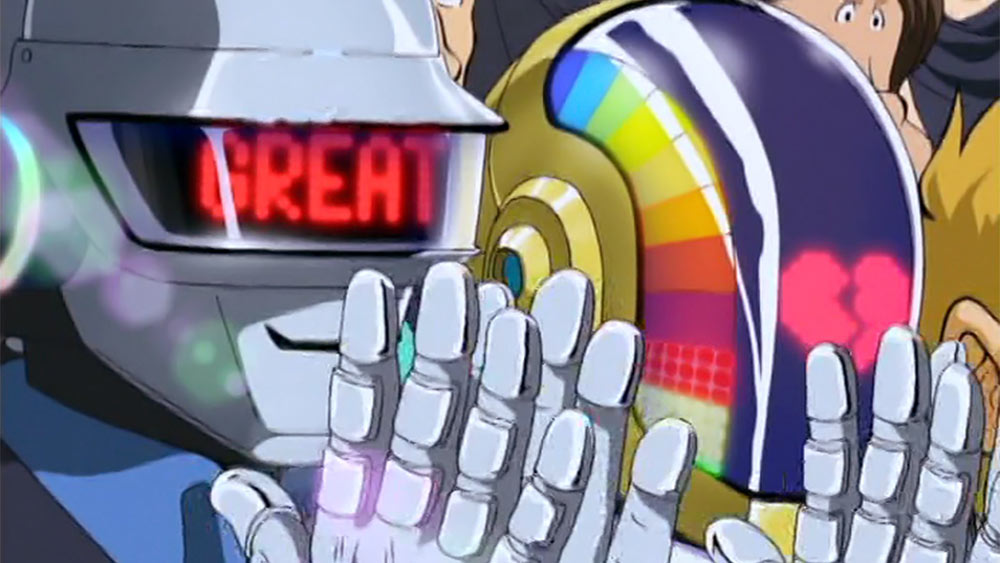

Film permeates even the character designs of Daft Punk themselves. Claiming in a Cartoon Network interview that an accident in the studio transformed them into robots, Homem-Christo and Bangalter have utilized the sci-fi helmets and gloves not necessarily to hide from fame or keep focus solely on their music, but also to create a larger fictional experience in their personas and live performances. The helmets premiered during their Discovery promotional period and were designed by French music video directors Alex and Martin and crafted by Tony Gardner, special effects artist and puppeteer. (Screen Slate readers may appreciate Gardner as having been nominated for an Academy Award for his makeup effects for Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa.) The artists claimed to be inspired by The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), another nod to the combination of futurism and nostalgia that runs through Daft Punk’s work. However, there is also the clear influence of Brian DePalma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974), one of the pair’s shared favorite films. The melodramatic rock opera, much like Interstella, centers on a musician attempting to live and create while maintaining the purity of his art, but has his identity stolen from him. Together they create a rather bleak image of the music industry as a vampiric cabal extracting artistry from naive performers, the very dynamic Daft Punk worked hard to circumvent through their characters.

—

That Daft Punk called it quits during COVID, as many push through the last stretch of winter by dreaming of a day where they’ll be able to hit the dance floor again and sweat among strangers, is sad but perhaps fitting. Many fans are unsurprisingly reminiscing about the Alive 2006/2007 tour, which was kick-started by the unveiling of the infamous enormous LED-fronted pyramid at Coachella 2006, a performance many critics cite as ushering in the mainstream era of dance music. From then on, large-scale electronic music festivals only became more and more popular. As gatherings of that sort still feel far away enough to wonder if they’ll ever return, the image of a lone beatmaker exploding against the desert sky seems pertinent.

To me (and I am admittedly not as versed in dance music culture as other fans of theirs), the heart of Daft Punk was always the magic of culture as curation-meets-coincidence: the gems you find by doing the work of digging through record crates, following a new friend to a late-night movie you’ve never heard of, or tracking down a foreign cartoon because you saw a cool illustration you couldn’t get out of your head. I stayed up late to watch a cool-looking anime music video because I wasn’t sure I’d be able to find out what it was if I didn’t, not knowing that doing so was exactly the kind of action that Homem-Christo and Bangalter were already memorializing. Daft Punk hit during the last gasp of media mystery, the second before actual robots started curating everyone’s cultural consumption. It turns out our android friends were human after all.