What follows is the amazing story of a lost gem of American film—one that comprises a student’s dream collaboration with William Burroughs, filming hardcore on short ends of stock leftover from Lenny, and an untested actor named Bill Paxton bribing his way out of jail in Tangiers.

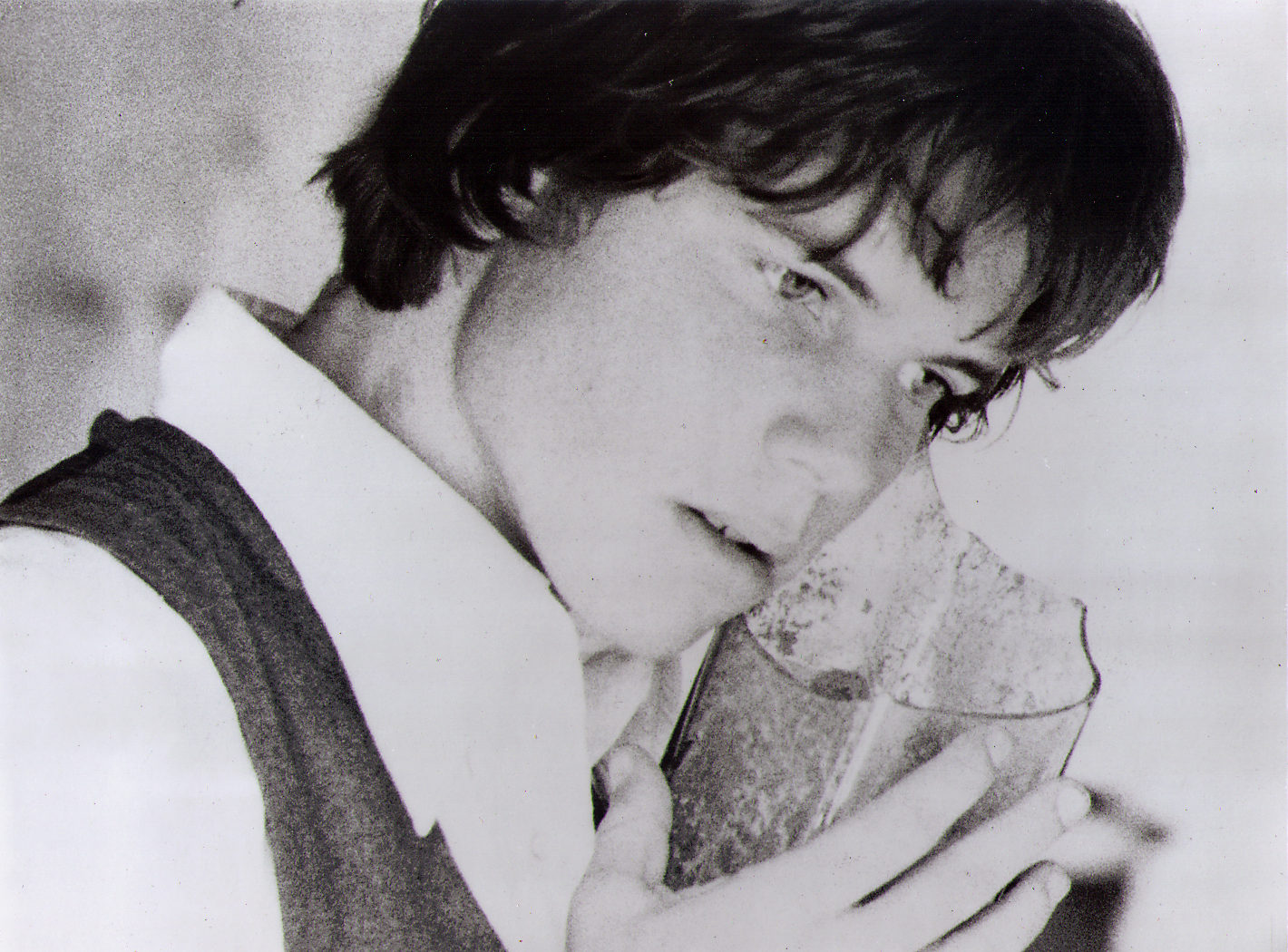

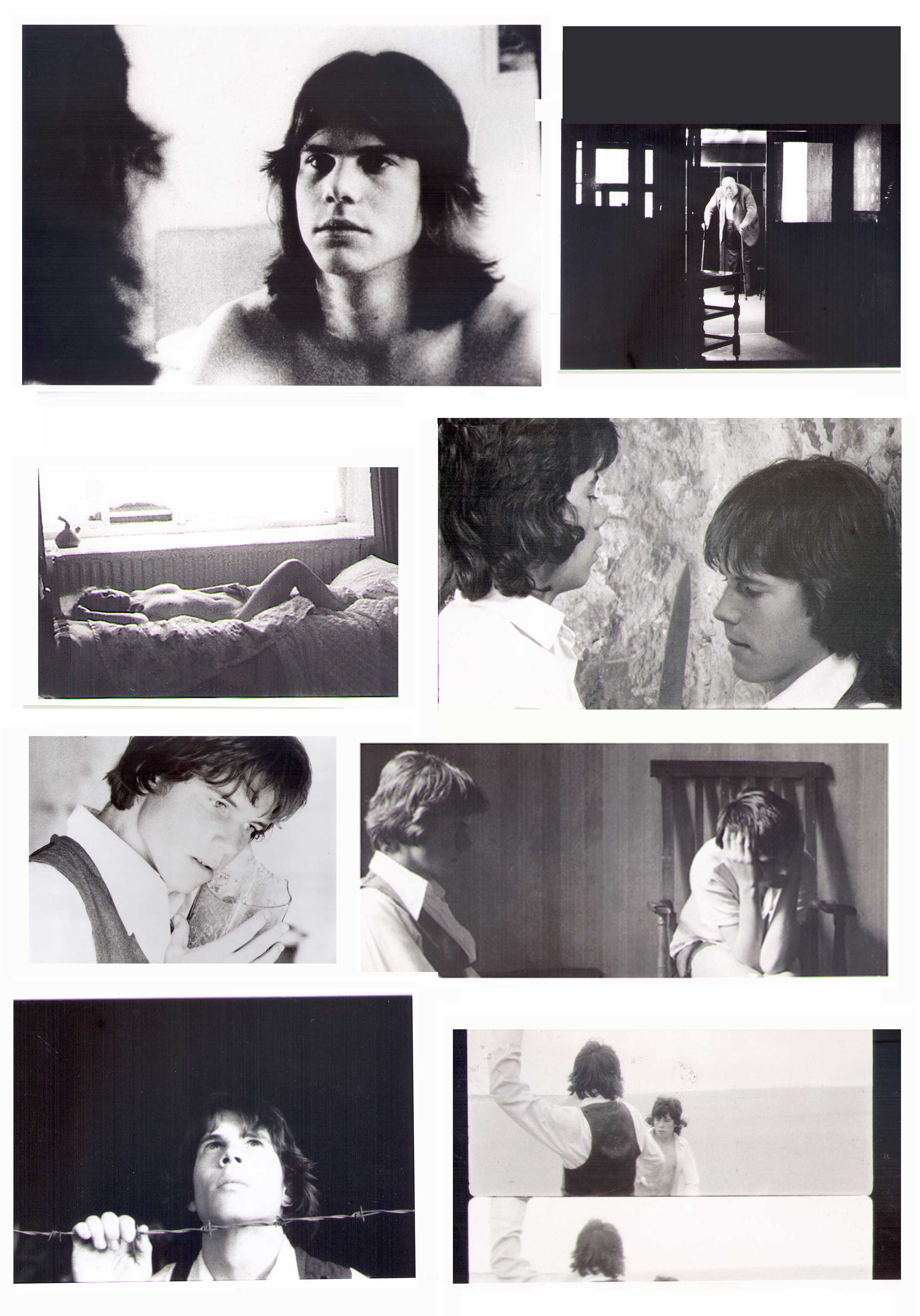

Under the spell of the French New Wave and ex-patriate writers like Paul Bowles, sometime in the mid-1970s Kent Smith and Bill Paxton resolved to fly to Tangiers and improvise their way through an experimental narrative film with the vague idea it would have something to do with the 1973 J. Paul Getty kidnapping. Smith had been directing educational films for Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Paxton, who had no significant acting experience, was an aspiring filmmaker and art director. The story of what happened follows in detail below; suffice to say, after bribing their way out of jail in Morocco and blowing through their film stock in Wales, they eventually relinquished control of the project to director Tom Huckabee, who in close collaboration with the duo re-conceived their silent footage as the backbone of byzantine eschatological nightmare. New lines were drafted, actors were recruited, and Huckabee hit upon the idea to glue the piece together with pervasive, dystopian radio announcements. His dream scenario was to fill them out with the words of his favorite writer, William S. Burroughs. One evening he casually relayed the idea to a friend-of-a-friend—who revealed he just happened to know Burroughs, planned to see him the following week, and would be happy to put the two in touch. With seeming effortlessness, a dream collaboration came to fruition.

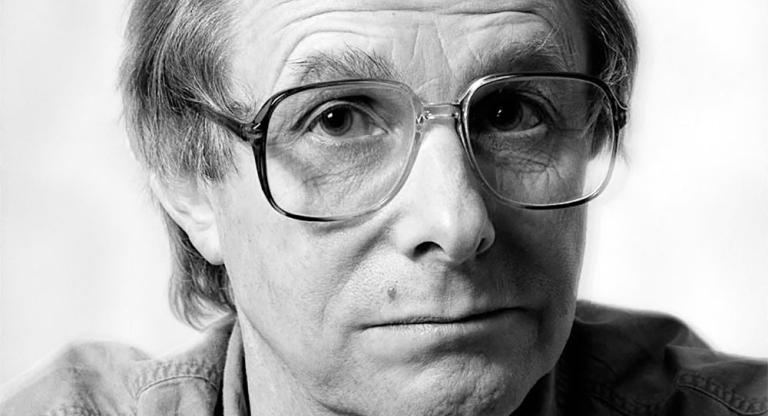

Burroughs has a colorful and varied history of cinematic engagement. Of projects realized on screen, there’s David Cronenberg’s acclaimed, big-budget adaptation of Naked Lunch; a slew of short films based upon his stories and audio recordings; a televised Austrian adaptation of The Black Rider, his theatrical collaboration with Tom Waits and Robert Wilson; and, perhaps most fruitfully, a number of short films made in direct collaboration with friends Antony Balch and Brion Gysin. Throughout his fiction there are innumerable references to cinematic technique and adopting the perspective of a movie camera as a narrative device. His novels Blade Runner: A Movie and The Last Words of Dutch Schultz expressly represent varyingly unorthodox attempts at screenwriting craft. Yet to date, Taking Tiger Mountain is the only feature film bearing direct writing credit for William S. Burroughs.

In truth, it’s hardly as if Burroughs sat at his desk under the muse of Syd Field and Robert McKee to crack out an apt 120-page script bearing three-act structure and perfectly blocked columns of dialog—yet the nature of his collaboration on the presumably scattered screenplay is certainly no more nor less reverential to the way films are supposed to be written than Smith or Huckabee’s is to the way they are supposed to be directed. Smith and Paxton set out to emulate Fellini and Truffaut, yet the end product approximates something like Joseph Cornell by way of The Wicker Man pervaded, at all levels, by the spirit of Burroughs. Depending on one’s orientation, the result is either a remarkably coherent work of experimental assemblage or one of the most singularly strange narrative films ever made.

In anticipation of the modest “New York City premiere” of Taking Tiger Mountain—from a cropped, vintage video transfer of a film for which only three prints were ever struck—Huckabee spoke with Screen Slate about the weird trip of the coolest film no one’s ever seen.

JON DIERINGER: I wondered if you could just start with a general overview of the production history.

TOM HUCKABEE: Ok! Be prepared.

It sounds convoluted.

It is very convoluted. In 1975 Bill Paxton and Kent Smith—Kent was 10 years older, Bill was 19—and Kent had a job with Encyclopedia Britannica films, and he had always fantasized about directing a feature. Actually, he’d been a classmate of Jim Morrison’s at UCLA. And indeed was very much enamored with the French New Wave, and Godard and Fellini may have been his two favorite directors. So he had managed to save a bunch of money off of one educational film, and he decided to make a feature. He wrote a long narrative poem about the J. Paul Getty kidnapping of I think 1973. That was when the grandson of Getty was kidnapped and they held him in a cave. After they didn’t get his money they cut off his ear and sent the family his ear, and once they got him back they figured out he’d been involved in the plot to make money off of his family. And it had just kind of gone bad, so they cut his ear off.

And was this original poem a more or less factual retelling of that?

No, no, just inspired by it. And Kent was also enamored with Middle Eastern culture. I think he’d read all the stuff by Burroughs and Ginsberg and Paul Bowles. So he decided he wanted to shoot it in Morocco, and he talked Bill into it. He thought Bill had potential to be a movie star. At the time, Bill was working for him as a set dresser or art director. He bought the short ends from the film Lenny with Dustin Hoffman, the Bob Fosse film. It was black and white, 35mm. Some of them were just rolls of 50 feet, 100 feet…

Was there any connection to the production, or is this just a coincidence?

No, there wasn’t. Some company had bought the film and sold it to him. Back then there were services that did that on a regular basis. It was very rare for 35mm black-and-white film to be made. Lenny was probably the only one made that year. [Smith] rented equipment: a silent 35mm camera, I can’t remember the brand of camera, and then they flew to Morocco!

…But neglected to call ahead. And you don’t just show up in Morocco to make a movie without preparing. Without paying off people, basically. So they were imprisoned and their equipment was confiscated and their money and everything. And all the film. I believe they were held for two or three days until Kent realized he needed to buy his way out, which they did. And they ended up in Spain down-on-their-luck, kind of yelling at each other…

And at this point had there been any preparation whatsoever? Was it more or less strictly like, “Let’s just get a camera and improvise something”?

Yeah! It was gonna be based on this poem. [Laughs]

So in other words, no contacting crew or actors beforehand?

No, no. Both of them were very adventurous people and… …yeah. It does sound a little—well, it was crazy. They’re in Spain pissed off at each other until Bill says, “Hey, I know this guy in Wales.” Bill and I had gone to school in England a couple years before and got to know a Welshman, and he had a cabin. His name was Barry Wooller, and he had a little stone cabin in Wales.

They drove to Wales, and it turned out to be in the boondocks. Hardly near anything but a bunch of little towns. They just started meeting people—actually, Barry became the production manager, and he started bringing in crew members and actors. Just townsfolk, really. His girlfriend played the main girl, Judy Church. Actually, I think that’s her real name, so she played herself. In fact, most of the townspeople kind of played themselves, and a lot of it was just being made up the night before. They’d be hanging out in the pub, and Bill would meet a girl and talk her into being in the movie, and the next day they’d be, you know, doing a love scene together.

They shot until they ran out of film and then came back to LA, which is where I saw it. The dailies. Basically, they felt like they were half-finished as far as getting through the plot that was in the poem. They tried to raise money to go back, which they never did.

Cut to four or five years later, and I’m in my last year of film school at UT Austin—

Can you remind me the chronology? When had they been shooting?

’75. So in ’79 I guess, I was in my last year of film school, and I really wanted to do a feature. I had this really cool post-apocalyptic short story written by an Austin-ite that had won an award, but I ended up losing the rights to that. Then I remembered Taking Tiger Mountain, which is what it was called all along. The inspiration came from the Chinese opera rather than the Eno album—[Smith & Paxton] didn’t know about the Eno album.

And what was the connection to the Chinese opera? I’m unfamiliar.

Not really anything…

The title just appealed to them?

Yeah, the title—it’s a shaggy dog story, and Kent’s forte was kind of elaborate non-sequiturs. He wanted things to be weird and strange and very instinctual. And I guess like Burroughs, sometimes he might just throw ideas up in the air, and however they landed is what he would do.

So when I got the footage, he gave it to me for a dollar. What prompted me to get the idea of buying the footage was UT had just acquired a 35mm flatbed Steinbeck editing machine. There was the capability to edit the film for free. I spent maybe a year going through the footage. There were 10 hours of footage, and I had seen it all back in LA and had been impressed by some of the images. I knew there was a lot of sex and violence and some exploitation elements. And I knew that a lot of it looked really good. But I also knew you couldn’t really finish doing what they were planning on doing. I couldn’t go back to Wales or whatever. I ended up just editing the ten hours down to an hour, until I had what seemed like—it was all silent, by the way. Kent was enamored by the way the Italians worked, especially Fellini, where they would just have the actors move their mouths, and then they would put in the dialog in post. So he intended to do that. There were a lot of dialog sequences, but I didn’t have a record of what the actors were saying, and a lot of them were speaking Welsh. So I edited it down to an hour that just seemed to flow in a natural way. And then came up with a story with the help of a couple friends.

Our story is about a young draft-dodger in the year—I think it was 1995 or something like that. [Laughs] The near future. From Houston. He goes to England to escape serving in World War III, which has broken out between the Americans and the Soviet Union. He gets kidnapped by a gang of feminist terrorists, a very sophisticated group. And they are at odds with the new common market government of the future, which has legalized prostitution and created these prostitution camps. In general, it’s a very patriarchal society, so they are creating time bomb assassins, and Billy Hampton is one of three of those. The assassins are sent out to these various prostitution camps to kill the leaders of the camps. So Bill’s character gets sent to some town in Wales. That was the concept.

We came up with this concept, and then I had to write and direct and cast and shoot the first ten minute sequence with the women. The stuff that’s on the video screen is from a short film Bill and Kent had made before they went to Wales, and I ended up incorporating that and making that into the scientific experimental footage the women are shooting as they’re documenting their brainwashing of the young man from Texas. So once I did that, I then had a 70-minute film. Back in those days, there was nothing you could do with a 70-minute, 35mm feature, so I ended up creating another ten minutes from outtakes, and those are some of those weirder sections of the film meant to just represent the disjointed, fragmented aspect of his brain from all of the experiments they’ve done to him.

Then I had to start deciding what the characters were going to say. Kent by that time had actually written a whole script with dialog, so in some cases I took the dialog he’d written and hired actors to sync it as best as possible.

Had he written the script to your edit?

He had written the script based on what he shot in order to go back and shoot the rest. So I took about half of what he’d written and then wrote the other half. But because it was supposed to be this patriarchal, dystopian, Big Brother situation, I decided there’d be constant propaganda being put out by the common market government via the BBC. A friend and I ended up writing all that radio voiceover that’s being pumped out everywhere.

Was any of the dialog improvised?

It was all very carefully written because it had to as much as possible fit the lips. Well—actually, Bill’s character’s voiceover was improvised. It came from his own childhood experiences. So when he’s musing on the soundtrack, and you’re hearing his inner dialog, some of that was improvised.

And this is all being done in approximately ’79? Long after the fact of the shooting?

Oh yeah. The entire story was all created after the footage was shot. It’s a completely different story than the J. Paul Getty kidnapping.

The way the Burroughs material came in was I was reading as much experimental science fiction as I could get ahold of—mostly Burroughs—and I came across this little novella called Blade Runner. And it seemed to be exactly the same world we had created. It takes place in New York City, but it seemed like stuff that could be going on in New York at the same time our story is going on in Wales. So I had the idea to put that on the radio as BBC broadcast describing what’s going on in America while Billy’s doing his timebomb assassin thing in Wales.

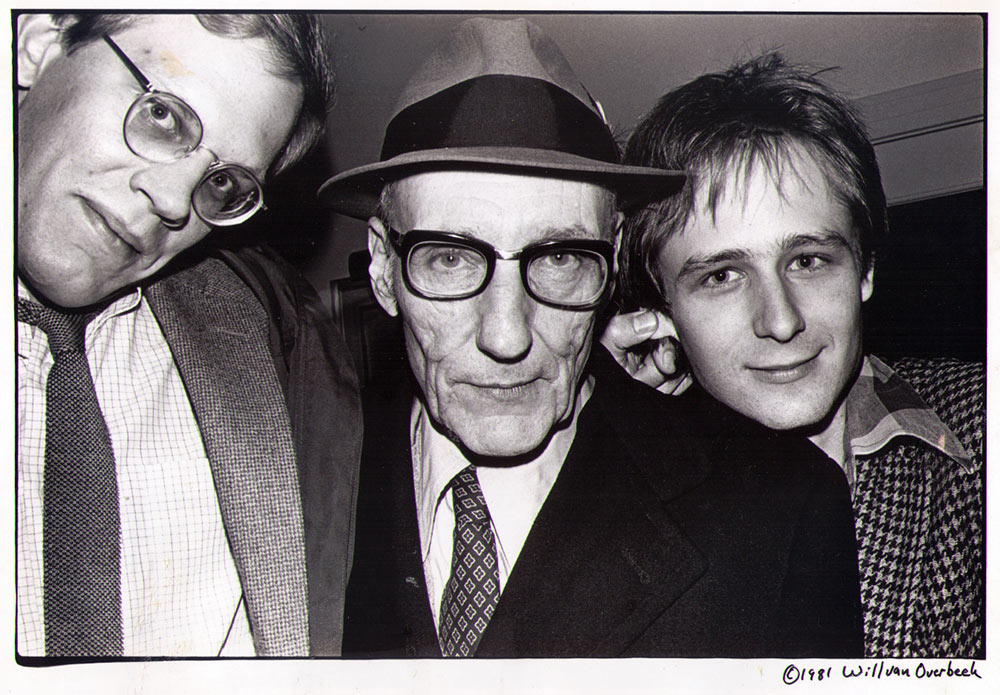

I didn’t have any idea how I could get in touch with Burroughs until a guy I knew—I was playing in a punk rock band called The Huns, and the bass player had a friend in town from San Francisco visiting. He comes and sees the show, and we were talking about Burroughs, and he said “I’m gonna see Bill next week, and I’ll ask him!” I was just flabbergasted. To me it was like saying you knew John Lennon or David Bowie or something. Burroughs was a giant star in my mind. And I had just published a book of poems with a poem called “William Burroughs is Dead,” which was inspired by what I knew about him. It’s kind of a cheeky, backhanded complimentary poem, you know. And I decided to send my book of poems along, and Adam was the guy’s name, Adam comes back and says, “So, I talked to Bill. He was offended by your poem, but he said you can still use his material.” And then he put me in touch with Burroughs’ secretary, James Grauerholz. I found out they were planning a book tour with Burroughs’s comeback book, which is called Cities of the Red Night. James Grauerholz had a whole lot to do with bringing Burroughs back into popularity during the 1980s. He got him on Saturday Night Live, got him that Nike commercial, got him in Drugstore Cowboy. So [Burroughs] became very open, and he was traveling the country, and a lot of young filmmakers were hitting him up at the time. He was very generous.

They came to town for a book signing, and actually while he was signing books at the bookstore I was flipping through a Moviemaker Magazine that had a picture of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner on the cover, and I was really surprised and shocked. I took it to James and said, “Did you know anything about this?” And he was kind of shocked, too. He knew [the Blade Runner production was] interested in the name, but at the time didn’t know the deal had gone through. Then we went over to the film school and I showed Burroughs the film. He was very complimentary afterwards and said, [affects Burroughs voice] “I think you got something there, kid.” He was really cool, he signed the contract, and I think I gave him $100.

The film did have a slight theatrical release. I ended up moving to Hollywood to finish the film—I had graduated, and I spent like two years on it at UT and they finally figured out what I was doing by postponing graduating in order to keep using the equipment for free. Finally they just gave me a diploma and sent me packing. It was actually cheaper to go to Hollywood and finish [Taking Tiger Mountain]. So I got back together with Kent Smith and worked out of his office. He helped a whole lot with the final leg of post-production.

And what was Kent doing at this point?

He was still making educational films. He’s never done another feature. I think he got real heavily into IT stuff.

What was your sense of his personal feelings about the project at this point? Had he totally relinquished ownership of it? Did he feel it was your film?

I think, you know, half-and-half. He came to the premiere in San Francisco, which was sold out. I think it was at the Roxy. And Bill Paxton came to that. I think [Kent] was delighted it was a sell out. I don’t know if he was ever totally happy with the film. None of us were, really. It was a true experimental film. And a lot of things were done kind of ass-backwards.

It’s so bizarre to me the how it is an attempt at a traditional narrative film, but ultimately almost more like a found footage exercise. It does seem to have some affinity with the whole cut up technique identified with Burroughs.

Oh, definitely. A couple of the scenes I did do as cut-ups. Some of the dream sequences I did throw the footage up in the air and stuck it together however it landed. So Burroughs really was the main inspiration for the style of the film. It really is very much like a lot of his later books, which are much more narrative-based but still with bits of cut-up. Of course they deal with a lot of brainwashing, dystopias and governmental influence. There’s all kinds of malicious organizations that are persecuting the individual. It really is in the universe of his later books like The Place of Dead Roads and Cities of the Red Night. I can imagine it easily being turned into a novel—it’d probably work better as a novel.

Burroughs also seems like a link to the initial conception with what Bill and Kent were doing going to Tangiers—being under the spell of ex-patriate writers and casting their lots with Morocco.

You’re totally right. I never really thought about it… I don’t know if that had been inspired by Burroughs. The main ones at the time were Godard and Fellini, but I’m not sure if Kent was a Burroughs fan.

When I hear Tangiers, I immediately think of Burroughs and Paul Bowles.

Right. And of course the other main Burroughs link is the homosexuality and the sadomasochism. Sexual confusion. There’s the androgynous character, Sally John, and the character Tony who is very sadistic and cutting people.

In a way, the spirit of that seems closer to Burroughs than even the way sexuality is handled in Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch movie. Which is a fantastic adaptation. But the key thing it lacks from Burroughs’s work is that engagement with non-heterosexual themes.

I think you’re right. I know that some of the bigger fans [of Taking Tiger Mountain] were gay and bisexual men that seemed to get it better than maybe other demographics. And then recently when I showed it here at the theater where Lee Harvey Oswald was caught—there were a bunch of ex-film students in their 30’s that all studied experimental cinema, and people like that tend to get it. I think when it first came out, it was just too weird. People mostly didn’t understand where it was coming from. I think when I show it these days, people tend to get it more.

There’s a willingness to embrace the weird more maybe. I mean, removed from the context of average moviegoing where you expect to see a certain presentation by a feature film—I imagine being pretty shocked going into this cold and expecting to see a narrative film.

Right. And another major influence on me was Alphaville.

I could totally see that. Actually, it reminded me of The Wicker Man.

Oh God, yeah! I love The Wicker Man. That had just been released when I was working on it, in fact it showed at a theater across the street from the film school. Yeah, I loved The Wicker Man.

Do you think it was a conscious influence at all?

Well… it was definitely one of my favorite films of the time. I mean, I don’t know. Of course it is in a remote part of Britain, and there is that malevolent character that can be a little bit like the major…

The remoteness of it, and the unsettling sense of being removed from home. The alienation, the atmosphere and tone of The Wicker Man are what really stuck with me, and I get the same sensation watching Taking Tiger Mountain.

[Spoilers] Well gosh, now that I’m starting to compare the two plots—the fact the whole town is aligned with the villain against the hero, who’s kind of trying to investigate something and ends up being, you know, killed at the end. So yeah, it’s very similar. [End spoilers]

Was the title always going to be Taking Tiger Mountain? Had you at any point considered calling it Blade Runner?

I didn’t call it Blade Runner because I couldn’t have gotten the rights because of the other movie. I did think about calling it Paradise Lost at one point. [Laughs] But I think Taking Tiger Mountain fits it really well since it is a shaggy dog story and that story is told at the end. I think it’s Taking Tiger Mountain—it couldn’t have a more perfect title.

This whole concept of the general, and the way tigers are incorporated through the film—is that something that was a response to Kent’s existing title?

Well, I knew we had that footage. Actually, Kent did go back to Wales. He was quite a world traveller and adventurer, and he did go back to Wales maybe a year after that first trip by himself. He got together with a bunch of the people that had been in the film, and he shot a bunch of 16mm sound footage of all the characters in character. And that was the only part of it that I used—the story of the major. I tried to incorporate some of the rest of it, but it didn’t really work.

And that’s what’s in the end credits?

Yeah. Cause that’s the only real sync sound in the whole film.

Which works well. It’s sort of jarring to see the whole movie where you have that effect of no sync sound, and all of a sudden at the end there’s more or less a direct monolog. It’s kind of a cool come down. A cool effect.

Yeah. And then the opening ten minutes with the women is quasi-sync sound in that at least the women are speaking the same words that were dubbed in later.

Was that shot on the same film stock Kent had used?

I think it was shot with a similar camera. Well… I think it was a different film stock. He used something that was out of date by the time we shot. It was called Techniscope. In fact, the camera he used was a Techniscope camera, which was created in the ’40s and was particularly created to shoot high-level documentaries in remote places because you only needed half the amount of film.

More portable?

More portable. And regular 35mm film has four sprocked holes, but if you cut the film in half each frame only has two sprocked holes. And it was a flat widescreen format. I don’t know if they ever had theaters that could show that… I really don’t know. Most of the widescreen New Wave French films were shot in Techniscope—Truffaut and Godard. It was very popular with them because it was cheap, it was half as much film. And you could use flat lenses. The anamorphic lenses were just not as crisp. But they’d all have to be converted when they were released in America, which is what we had to do. We had to convert all Kent’s footage to anamorphic, and then I actually shot in Anamorphic. And that’s one of the reasons why it looks different. The other would be because he shot almost entirely with available light and very high speed film, so it’s grainy. But it’s also gone through more generations than that first ten minutes of footage.

Could you give me a little bit of history about the print? Is there only one?

No, there are three 35mm prints. The video you’re showing was created for film festival entry, and that was mastered on 3/4″ tape. I had the choice at the time—I got in afterhours at the place—and I had to make a choice between going widescreen, and at the time no one had big TV’s and of course no one had widescreen TV’s. Usually what was done is pan-and-scan, but that would have been ten or twenty times more expensive. I had to choose between widescreen, which of course would have been the right choice [Laughs], or just showing the middle third. And so I ended up going with the middle third, or it probably comes out to more like half. So we couldn’t move it and we just had to set it in the middle of the frame and let it roll.

Kent was using the full frame. He never expected the film to end up on TV or video because of the transgressive nature of the material. There just weren’t X-rated films being shown on TV, and [the time of the shooting] was even before the porno revolution. An art film with X-rated footage was properly unheard of except in Landmark movie theaters, which is where ended up showing it. There was Salo, which was the last film that was ever confiscated. It was literally arrested, the film itself was taken to jail in Houston, and the projectionist was taken to jail. And that was the company I was working for at the time, Landmark. When I got to Hollywood I brought Taking Tiger Mountain and showed it to them, and they decided they wanted to put it on their circuit, and they ended up hiring me as an in-house producer. So by the time it was playing on the circuit, I was working for them. And during the time I was working for them Salo was arrested, and it went to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of free speech. And it was the last censorship trial I think.

It had a great review and a great run in San Francisco, and it played on the Landmark Theater circuit. And then just kind of disappeared for twenty years or more. But that video was created just for film festivals so they could get a sense of it. It was meant to be shown on 35mm, which is part of the reason I’ve never put it out on video. But the main reason is I’ve never been able to afford a good transfer.

So Landmark wasn’t the distributor, was it? Were you self-distributing?

No, it had a distributor that was associated with Landmark. They were called Horizon Films. I know they had something to do with releasing the first Decline of Western Civilization. So they handled kind of edgy, low-budget art films. They were a perfect distributor, but it also just happened they went bankrupt during the release, so… [Laughs] And also during the release I was having a lot of stomach trouble, and in fact during a live camera interview I had a terrible stomach attack and had to be taken to the emergency room. Which we later found out was appendicidis. So during the release… it may or may not have gotten more attention, but I was suffering from appendicitis.

It did play at the very first Independent Feature Project market in New York City at the theater in Columbus Square. It didn’t get picked up by then by anybody. Never ended up being distributed in Europe. The only distribution it’s ever had is domestic theatrical.

So the distributor went bankrupt during the release?

Yes.

And the rights just reverted back to you?

Yeah.

That’s not a bad deal.

I’ve been approached a couple times by people who wanted to release it, and the biggest issue is just the transfer. If anybody was willing to put up the money for a decent transfer, I’d be all for it.

The other thing I think is really great about the film is you get an entirely different picture of who Bill Paxton is. Bill is a friend, and I know he’s kind of ambivalent about the film for various reaons, but at the same time I think it really shows you where he came from, which is a very artistic background making experimental films. In fact there are several films he and I made and that he made with other people that are really cool. There’s a fantastic experimental film he made right after he shot Taking Tiger Mountain with a guy named Rocky Schenck called The Egyptian Princess. It won an AFI award—40 minute film shot on Super 8 black-and-white blown up to 16mm. I’m pretty sure you can stream it on YouTube. It’s really cool, and I think when people see Tiger Mountain or The Egyptian Princess they get a different picture of who Bill is.

I’ll tell you one funny thing about Burroughs—he thought I was going to ask him to record his parts himself, and at the time I didn’t think it made sense. And it still doesn’t make sense. But I wish I’d done it. [Laughs]

I totally see what you mean about it not making sense. But I suppose in a way, his voice has become sort of iconic. He’s not James Earl Jones as Darth Vader or anything, but…

It’s a shame nobody ever made a movie starring him. There are documentaries and of course Drugstore Cowboy, where he’s used beautifully. That would have been a great movie to take that character and make a feature out of it.

It’s really bizarre to me how few film adaptations of his work there are considering how cinematic his work is—Wild Boys, Exterminator, Dutch Schultz… To varying degrees, they all make use of cinematic techniques and describe camera angles.

Well, you know, Wild Boys became a Duran Duran song and music video.

Ha! I knew of that, but I haven’t seen it.

At the time there were a lot of low budget student films that were made off his material. When he gave me rights to [material from the novella] Blade Runner, I knew there were a few other filmmakers on my level that he gave the rights to various stuff. Who knows if this stuff still exists or not. The way to find out would be to contact James Grauerholz.

As far as I know this is the only feature film with a writing credit for William Burroughs.

No kidding?

Naked Lunch obviously is based on his book, but it’s not credit to him as writer. David Cronenberg’s screenplay based on William Burroughs’s book.

That’s fascinating, I didn’t realize that.

And a lot of different little shorts. He had done a bunch with Antony Balch.

Well, Burroughs was extremely approachable and generous. He was just so easy to deal with. And James was such a great businessman and promoter, and he made it all run smoothly.

It’s nice to hear that and to think that at the same time as he’s doing things like SNL and Nike and book stores they made it an equally a priority to connect with other upcoming artists.

James was a punk rocker, and I think he was in a band briefly with Lester Bangs. He was part of the whole CBGB scene. When people are talking about William Burroughs and his resurgence, they’re really talking about the combination of James Grauerholz. He was his editor, he was his factotum, he was his best friend, I think they started out as lovers. But James was just a brilliant promoter. He really recognize how important Burroughs was and how to support him.

Sunday, March 25 Screen Slate Presents TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN featuring a Q&A with Tom Huckabee at Spectacle Theater, 124 South 3rd Street, Brooklyn, NY, 11211. It will be presented on a cropped video transfer that represents one of the few known extant elements of the work. The screening begins 5:30 pm sharp with $5 cash admission at the door. Check out a brief trailer here, and RSVP on Facebook.