Today the Museum of the Moving Image presents a program of films by Ken Jacobs, one of experimental cinema's most uncategorizable figures. The Brooklyn-born filmmaker helped define “underground” cinema in the 1960s with films like Blonde Cobra — a wild, ramshackle work of trash art featuring Jack Smith — and later, his found footage reconstruction works, most notably Tom, Tom, The Piper’s Son (1969/71), became key structuralist films. Through filmmaking, performance, teaching, organizing, programming, and more, Jacobs has explored moving images for more than half a century; his place in the American avant garde is central and his influence is incalculable. MoMI’s program, “Double Wow and other works by Ken Jacobs,” showcases several distinct dimensions of the filmmaker’s staggeringly diverse, seemingly inexhaustible output.

The film Double Wow is a new, 40-minute, purely visual 3D experience that evokes a kaleidoscope in slow motion. In the work, familiar images — trees, leaves, fences, geometric shapes — stay on screen long enough for the viewer’s eyes to explore the contours of the illusion. Jacobs, who was a student of ab-ex theorist and painter, Hans Hofmann, has long been interested in the phenomenon of 3D film; with Double Wow, the filmmaker creates an abstract, Hofmann-like portrait of space rendered in time using digital means and 3D technology.

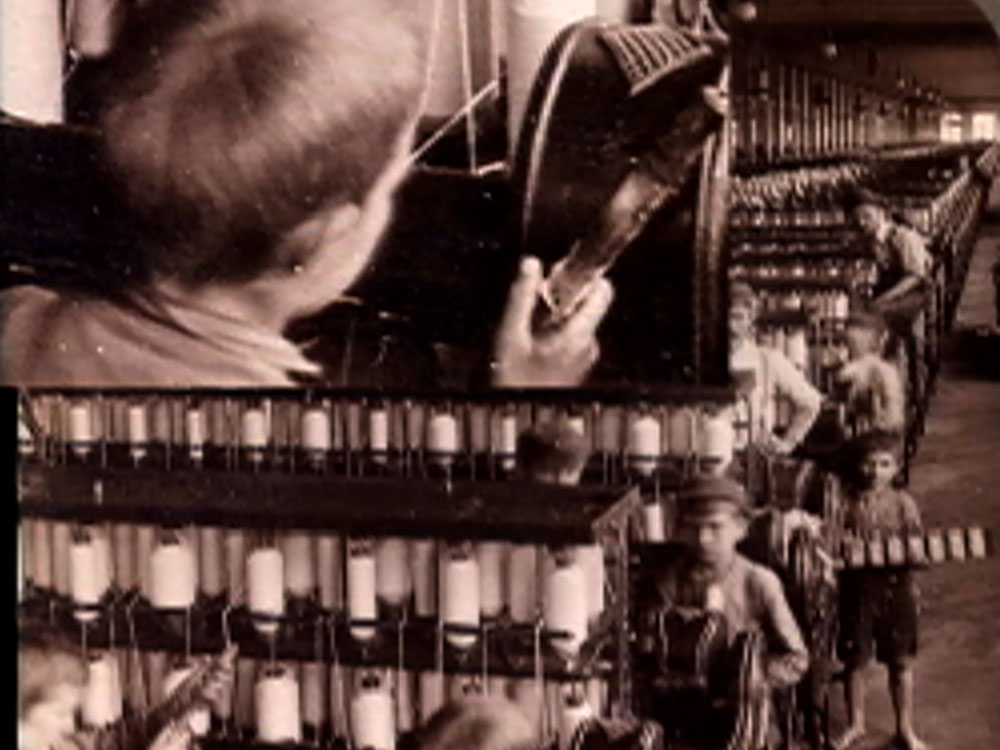

In Capitalism: Child Labor (2006), Jacobs exhaustively explores a single still image while creating the illusion of movement and three-dimensionality. The image in question is a stereoscopic photo of a turn-of-the-century factory floor where children are at work. Through continuously resizing the image, making it larger in one frame and smaller in the next, the film creates the sense of constant movement and a seemingly endless landscape of misery and repetition, conjuring industrial capitalism at its core. It’s a powerful and hypnotic filmic indictment of labor exploitation and the economic system (ours) that birthed such mechanized hellscapes.

Along with these expressly optical works, the viewer is treated to a more intimate side of Jacobs’ output with Spaghetti Aza (1976) and Nissan Ariana Window (1969). Nissan uses footage of Jacobs’s family, sometimes staged, sometimes seemingly candid, to create a painterly vision of domestic life. We see, for instance, Jacobs’s pregnant wife, Flo, posing nude for a cinematic portrait, when a cat unexpectedly enters and sits at her feet. Later, Jacobs simultaneously captures and creates a real-life silent comedy as he attempts to get his infant child to sit still in the center of the frame. It’s moments like these that make us feel the tension between unpredictable play and formal engagement that makes much of Jacobs’s work so unique and alive.

Double Wow and other works by Ken Jacobs screens today as part of Museum of the Moving Image's First Look 20/21 festival.