Dash Shaw began publishing comics while a student at SVA and made a splash with his 720-page doorstop Bottomless Belly Button (2008). Then came BodyWorld (2010), a serialized pulp science fiction narrative revolving around a drug which allows one to experience the physical sensations of another. New School (2013) is a Jurassic Park-inflected narrative of cultural conflict and coming of age, Doctors (2014) imagines a momentary medical triumph of life after death and its consequences, and Cosplayers (2014) explores a friendship mediated by popular culture.

Shaw’s visual approach to each new work is as unpredictable as his subject matter, but he regularly overlays simplified linework atop textured painted imagery that ranges from the gestural to the abstract. His aesthetics partly emerge from his fondness for traditional cel animation, and particularly for the limited animation techniques that characterize the medium’s most budget-conscious, televisual manifestations. It is therefore no surprise that Shaw has worked in animation for much of his career. Beginning with a series of 2009 shorts for the IFC channel and an animated music video for Sigur Rós, Shaw’s motion picture work embarked on a dialogue between comics and animation that culminated with his first feature film, My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea (2016). Adapted from the narrative of one of his short comics, High School Sinking brought to film the animation-inspired aesthetics that Shaw developed within the comics form.

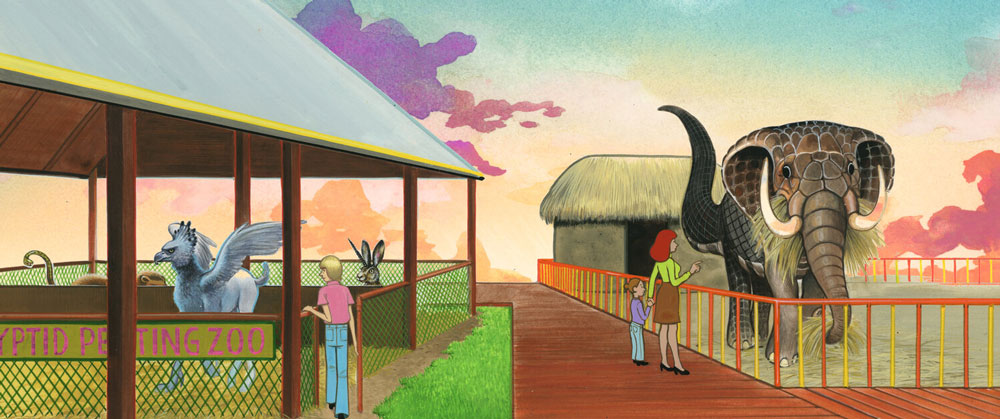

Shaw’s new film Cryptozoo embraces a different set of possibilities, incorporating a range of visual styles that showcases the unique strengths of his collaborators. Its release very nearly coincides with the publication of his forthcoming graphic novel, Discipline (New York Review Comics), a sparely drawn, black-and-white meditation on a Quaker youth who defied his religion’s pacifist philosophy to fight in the Civil War. And, later this year, Uncivilized Books will publish New Realities: The Comics of Dash Shaw, a book-length examination of the artist’s work by critic Greg Hunter. I was grateful to have a chance to talk to Dash at this pivotal moment in his career.

Cryptozoo opens Friday, August 20 on digital and at Angelika Film Center, BAM, Nitehawk Cinema Williamsburg, Syndicated, and other venues nationwide. Thursday, August 19 the Rockaway Film Festival presents a free screening followed by a Q&A with Shaw moderated by Kartalopoulos.

Bill Kartalopoulos: Over the past few days, I watched Cryptozoo and read Discipline.

Dash Shaw: Oh, great.

They both seem to engage the things that are different about comics and animation. In My Entire High School Sinking into the Sea you took aesthetics from your comics and brought them into animation, whereas in Cryptozoo and Discipline that back-and-forth wasn't there. With Cryptozoo, you were really making an animated film, and with Discipline you were really making a drawn book.

Anything that I would say about that, I would feel like I would be kind of making up something after the fact. I didn't consciously finish these things around the same time. I started Discipline while I was still drawing High School Sinking. Discipline took so long, and I didn't know when Cryptozoo would be done. But I think something that you're pointing to is, I would never do Discipline as an animated movie.

Having been raised a Quaker, the main thing that is associated with Quakerism in my mind is silence. As a little kid—a three-year-old—to be able to sit in silence for a long time, you really, really get a strong muscle of quietude and kind of a sense of activated silence. And I think comics, something that they can do very well is have a silence in them. And so I really tried to lean into that with Discipline and make it a goal to see how meaningful the silences could be in that book.

And then, I feel like books are very internal and films are very external. I think of the two movies I made as blockbuster movies or “go out on Friday night and see that in a movie theater with some people” movies. I want to deliver a spectacle. Whereas a book, it's at home, alone on a Tuesday night, sitting in your chair. It's a different experience.

Silence is both a strategy of your aesthetic process and a theme in Discipline. There're so many wordless sequences throughout that.

Whatever you just said, I'm glad that it's recorded, because I think that says it very well. And I'm going to steal it when I have to talk about the book.

What got you started thinking about cryptids as a subject, and what made you think this was an idea for a film rather than a book?

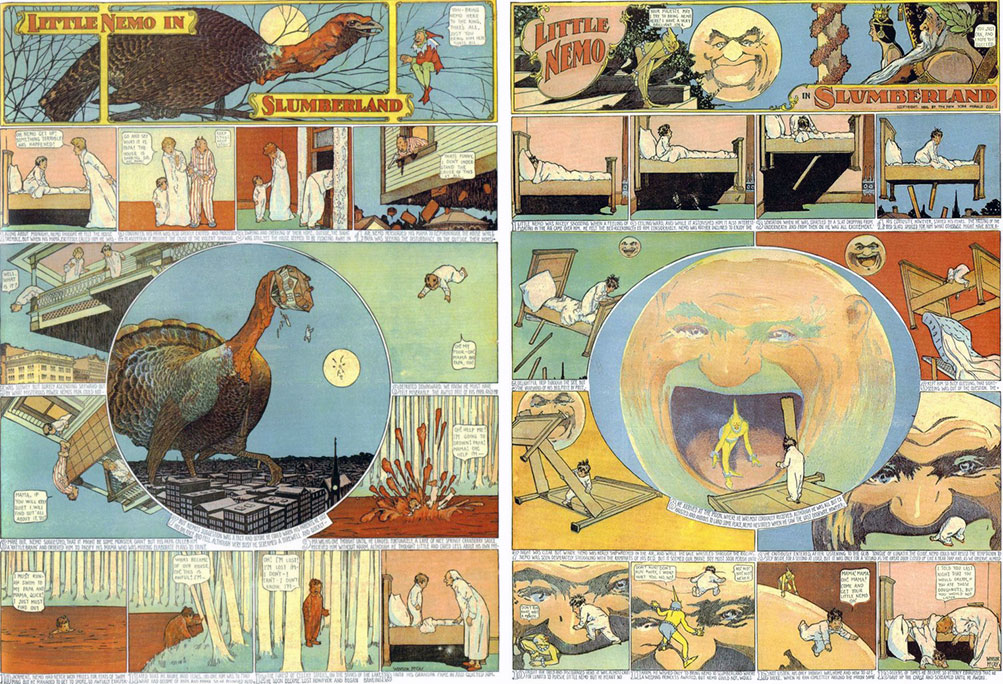

I had seen this early Winsor McCay short called The Centaurs from 1921. And the fact that it was unfinished was exciting, and that it has the kind of adult sexy quality. I think it might have inspired the centaur sequence in Fantasia, because it has kind of these half nude centaurs and almost looks like it could be a photo collage forest background.

Winsor McCay, for some reason, just keeps sticking around. Every time I move and have to decide which books to take with me, I take that Little Nemo in Slumberland Sunday collection. Even though I think that the writing in a lot of it is not worth reading, it's still full of this graphic invention and imagination and playfulness that one hundred years later is still inspiring.

All of his projects are kind of leaning into what drawing can do that other mediums can't, by depicting dreams in Little Nemo or using drawing to resurrect dinosaurs for Gertie. Here's this master who saw drawing as our only way of depicting mythological beings that can't be photographed. That was exciting. And there were a bunch of different cartoonists doing kind of Sunday-page-style comics for a while there, and I had never done one. And I thought maybe I could do something where each page is a different cryptid, a different mythological being.

Then, when I was looking into that, I came across the Baku. There's an 1800s drawing of a Baku by Hokusai. And a dream-eating creature then suggested a movie. Because I think movies can really create a dreamlike atmosphere more than a comic. A comic, you're always decoding. And you always have a bit of an analytical brain going on. Because the words are so different than pictures, and you’re often stopping and orienting yourself: “Do I read this before I look at that?” or whatever. But a movie—even just a cut in a movie—is a weird, dreamlike leap of logic that is thrust on you. So, the Baku really made it a movie idea and not a comic idea.

Also, Jane, who's the animation director, painted most of the cryptids in the movie. I wanted to write something that she would enjoy participating in. And I knew that she would love painting all these creatures. She had an all-women's D&D group around them. And so I was trying to write something that she would be psyched about.

The film is presented as a film by Jane Samborski and yourself; she's the animation director and also your partner. Can you describe that division of labor? How much of this did you do within your own home?

Well, my studio is a room on the upstairs of my house. So, it's kind of all in our home. And during the process of High School Sinking, we figured out each other's strengths and weaknesses and kind of sectioned each other off. I'm terrible at computer things and organizational things, and Jane really excels in that area.

So, trying to describe it, it's two people coming from very different places that are somehow meeting in the middle. She always wants things to be more—more animated, move more—and I always want things to move less. I'm always like, "No less, less." So, I think that's just one example of many—conflicts is too strong a word, but differences where I think the movie is better for meeting in the middle.

High School seemed a little bit more like an indie comic book, the film equivalent of something that could have been made by one person, whereas Cryptozoo almost felt like an anthology. There was more aesthetic diversity. There were many hands involved that were allowed to have their own distinctive visual style and expression, all those names that scrolled by at the end that I recognize from reading comics, people like Frank Santoro, Sophie Franz, Ben Marra, Jed McGowan, and Robert Beatty. Did you go into this project thinking of it as something that would rely on the strengths of other people more than your previous film?

Well, I definitely tried to write something much bigger. High School Sinking was written thinking, "If it all fell on me, I could paint those backgrounds”. We got great other artists involved in that movie, but if we couldn't get them I could have cobbled it together and figured it out.

With Cryptozoo, I hope that part of the fun of the movie is that for something that is very obviously a small-scale independent film operation, we’re going all over the world. There're so many things going on, so many creatures. So, I hoped that that would be some of the fun of the movie. And, while it has these different artists, it's like a Ralph Bakshi thing where the movie isn't all over the place, because the people are being very specifically cast. If you watch Wizards, you can tell that some backgrounds were drawn by specific people who didn't paint the other backgrounds in the movie, but it doesn't look like a mess. It looks like it was a well-cast group of artists. Ben Marra painted all of the motorcycles and stuff in Cryptozoo, and I know that he knows motorcycles and rides motorcycles, and I knew that he had this kind of painting thing that he wanted to do. So even though we did pay the artists something, you're still asking someone who's your friend to participate in your project. So, I tried to cast it in a way where they were bringing their identities and their personalities into the project, and I wasn't asking them to draw like me.

You've always mixed visual codes, even in your comics that you've drawn yourself. Going all the way back to Bottomless Belly Button, you have a character who is drawn as a frog whereas other characters are human.

Cryptozoo is also about conflicting visions. You have these characters who are in competition with one another regarding their approach to cryptids—the people who want to offer sanctuary, the others who want to just straight up exploit them—but at the same time there's a questioning of the superficially benign motive as another form of exploitation. And the movie is set in the 1960s or early '70s, during that countercultural period, which ties into the psychedelic aesthetics of the film and the kind of "hippie idealism" that one might critique and realize actually perpetuates colonialism or other forms of inequality and so on.

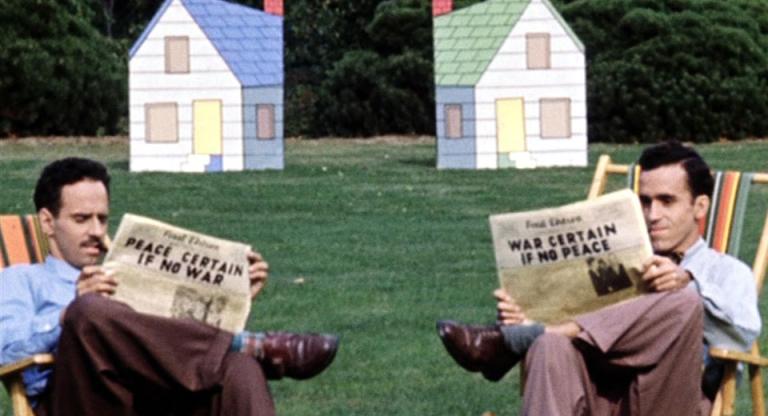

Well, absolutely everything that you said is what I consider the content of the movie, and fitting this inside of an hour and a half long, experiential, fun spectacle movie is the goal. When I was researching Discipline, I had a fellowship at the New York Public Library and one of the other fellows there was researching countercultural newspapers of the 1960s. There would be a 1967 free weekly paper from Brazil, and another that same week from Chicago, and they all had an incredible optimism. Sometimes, the titles would be just one word, like "Progress” or something. So, it's hard not to look at those now with a melancholic edge of kind of us knowing how it all went down. Robert Crumb is in tons of those free papers. And when we think of Robert Crumb now, we think of very different things than what he was associated with at that time. So all of this is to say that I tried to create a network of characters that could have this kind of conversation and have that be the middle section of the movie. And that I would be kind of carrying that melancholic feeling inside of, the kind of disaster movie structure of us kind of knowing at the very beginning that the Cryptozoo isn't going to work out. And we're going to see how it falls.

We talked already about how you invited these other artists in and you didn't want to suppress their aesthetics. You're directing an animated film that you've written and you're bringing all these other artists in and it's becoming this more collaborative approach. To what extent is it still important for you to see your own style in the finished work?

That's a really good question. I try not to think about what my style is. And often, the kind of dirty secret about drawing is that a lot of what your drawings look like depends on the practical decisions of this kind of tool on this kind of paper done at this particular scale.

So, the book New School that I did looks very, very different than Discipline, because New School was drawn with a very thick line on smaller sheets of paper and Discipline was drawn with a thin crowquill line on larger sheets of paper. And so your hand just kind of naturally makes different marks. But in the context of a movie, the style ends up being kind of the orchestration of all of these elements, just like how a live action filmmaker has a particular style, where it's how they're arranging all of these humans.

And the fact that a lot of the figure drawings are my drawings or some of the background paintings are my paintings is not, I would say, personally important to me. I bet other people could have done those elements and I would still be happy with the end result, because it's in the orchestration. It's hard for me to say. I storyboard the whole film, so just that is a lot of labor and many personal decisions at every stage. And when I'm talking to different artists, I have to kind of articulate what I'm asking them to execute. So those are kind of more where the personality is present.

What I liked about independent film initially was not that it felt like it was made by one person, but that it was the power of harnessing less-is-more. Godard could just use these very simple tools that all filmmakers had, but somehow he found very profound ends for them — from how these two images are cut together to how music and image are paired with each other.

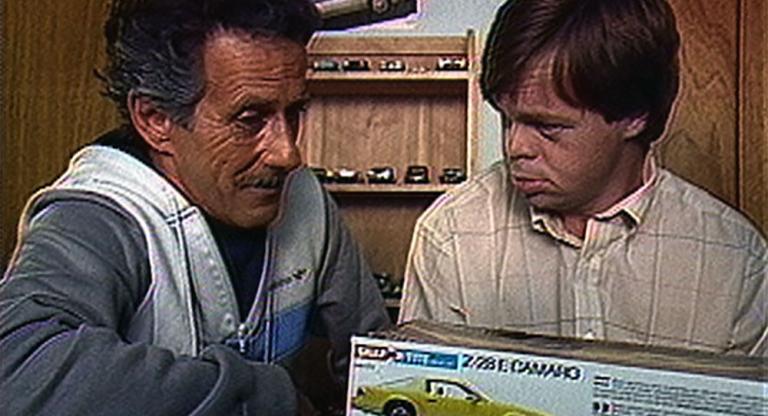

Thomas Jay Ryan struck me as a real MVP across both High School and Cryptozoo, someone who turned in striking, nuanced performances that made these antagonists kind of quirky and almost sympathetic. I remember him very well from Hal Hartley films and haven't seen him much outside of that. How did you end up working with him? Did you have him in mind when you were developing his character in Cryptozoo?

I did have him in mind. I had worked with him in High School Sinking and I really love him as a person. He has kind of an alternative cartoonist personality, a very endearing attitude. Hal Hartley found him from all of that experimental theater in New York at that time, where Thomas Jay Ryan would have to say a line while lifting one leg in one corner of the theater. And that's present in a lot of these Hal Hartley movies that have a kind of dance quality to how the conversations are done that was super, super appealing to me. I first saw those as a teenager and I didn't know who Godard was, and it introduced me to so many of these things about independent cinema that I really love.

I also appreciated that the Gorgon character, Phoebe, was voiced by a Greek actress. There has been a lot of Greek-mythology-themed media in recent years, but not much representation in that area.

Besides the main reason of Angeliki Papoulia being an incredible actor — and speaking of another filmmaker I totally love, I think Yorgos Lanthimos’s movies are incredible, especially Dogtooth — the idea was that we weren't inventing mythological beings, that all of these mythological beings are from actual mythologies from our actual world. So many fantasy movies you watch are in this allegorical space, and you can kind of watch it from afar. With this one, I wanted it to be like reality was constantly intruding on this fantasy world that's our world. And that combination would be exciting and disorienting.

The climax of the film has a very psychedelic aesthetic to it. Were there any aesthetic reference points that informed the fantasy aspects of the film? I was reminded of Asparagus or Fehérlófia, or Fantastic Planet, or even books like Barlowe's Guide to Extraterrestrials.

Well, definitely in how the cryptids were physically painted I was thinking about Fantastic Planet, because that's technically a stop-motion film. But because all of the pieces are painted it doesn't look like stop-motion, and it looks like a Hieronymus Bosch painting come to life. I think Asparagus by Suzan Pitt is one of the greatest films of all time. I've watched that movie many, many, many times. In retrospect, there's a stage in Cryptozoo that's a physical stage that was built and photographed. And I didn't intentionally pull that from Asparagus, but Asparagus has a scene in a theater where it's a physical, 3D theater that's been photographed. So that could have been why I chose only that one real environment in Cryptozoo. There're so many things going by at once in Cryptozoo that I think it just becomes part of the language of the movie, and it doesn't particularly stand out.

A lot of times I'm trying to figure out how to execute these things. Often the way something is communicated in video games makes sense. Like the tarot card sequence. I think that as being from solitaire computer games, when you see the cards being shuffled. I grew up not playing a lot of games but watching other people play games. So, I kind of took it as more of a cinematic experience than a story experience. And then it also has a force of connection to a kind of limited animation where you're trying to communicate a lot with limited means.

I want to go back to Discipline. The text itself is more narrative than dialogue driven. Often it's epistolary, in the form of written letters with a lot of silence throughout. You mentioned before that you were doing research at the New York Public Library, as a Cullman fellow. Can you talk about your library research for this book?

Yeah. Again, I was raised Quaker in Richmond, Virginia, so I knew about this moment in time where there was a rift in the Quaker community about whether or not to fight in the Cvil War for the Union, because Quakers were famously anti-slavery but also pacifist. So that seemed really interesting, of course, but very, very intimidating as a subject matter — besides just, like, drawing horses and everything. I thought it was a story that felt specific to me, and that if I had the cartooning skills, maybe I could pull it together.

And then when I applied to the New York Public Library, they said, "Oh, we have an archive of Quaker letters and diary entries from this time." So fantastic. So, I went there and I read a bunch of them. And that was the main twist in thinking about the book because you would know from the records that there was a giant, horrible battle that day, but the soldier just wrote what they ate. And so, as I researched it, it kind of became more unknowable.

The Civil War-era journalists of that time are called “The Specials.” They were meant to do sketches on the battlefield and then they were sent to a team of etchers for the newspapers. Some of them just sat at home and BS'd war sketches and sent them to the editor. I realized then that because of what I was looking at and my personality, I couldn't do a book like Louis Riel by Chester Brown, which I love. Meaning I couldn't do something that was an educational or fact-based explanation of what was happening during this rift, that it was going to be something more about the dissonance between what people were writing and thinking and what was happening. Also, in a lot of the Quaker writing from that period, they're saying these very idealistic things that are kind of hard to grapple with.

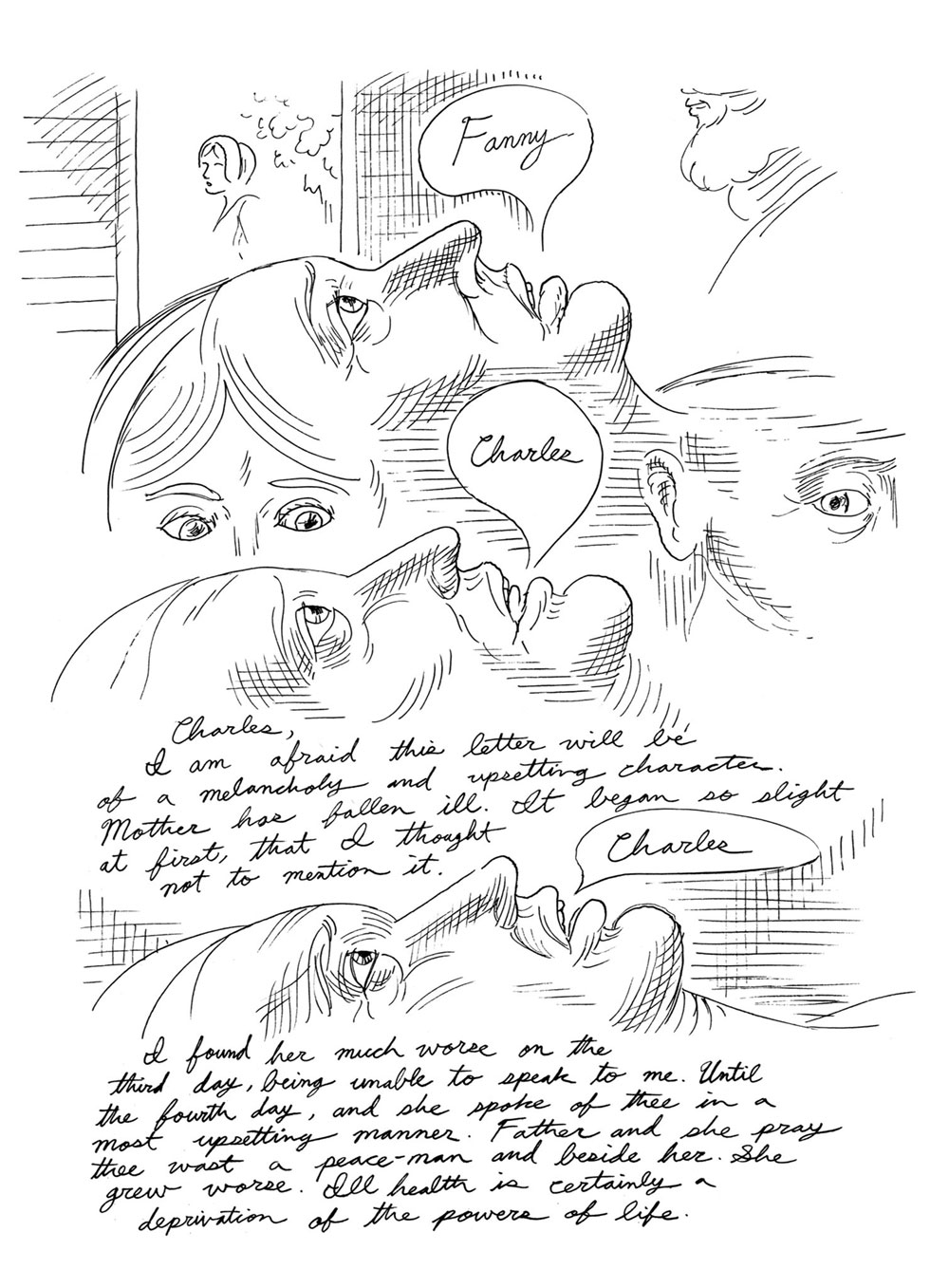

So, I think that if the book is doing something, if it’s contributing anything it's leaning into that dissonance and those juxtapositions. So, a lot of the text is coming from actual Quaker letters and diary entries from that time, and it's being paired with imagery. So, ideally, it's kind of in between spaces.

A lot of the text is presented in the form of letters, or internal thoughts that feel like diary entries. And people being moved to speak in a Society of Friends Meeting House. It feels almost like monologuing. There's very little actual dialogue in the book. Were you drawing from the types of statements that were made in the letters and diaries?

Yeah, often I'm just kind of taking sections from letters or diary entries. Especially, it comes from a book called The Fighting Quakers that was published in 1867. That's the actual correspondence of two Quaker brothers with their mother. But I would alter it to fit it into a narrative. I kind of cheated a bit, because I have the main character in his mind staying Quaker when he leaves. And my reasoning behind that is that if you're raised in a very small community and then you leave that community, part of your mind stays back in that community. So that's my excuse for why he is thinking a bit more deeply than what I read in a lot of these actual diaries.

Even though this seems like a much more aesthetically consistent work than Cryptozoo, it sounds like you're talking about an element of collage here too where you're taking bits and pieces from this found text. And then the way you arrange the images on the page is associative and collage-like, also.

Totally. Because also, a lot of Civil War era illustration doesn't have borders. All of the drawings float. And I knew that if I spent three years researching this thing and penciling it all out, I just wasn't going to finish it, that it would be giving myself this giant illustration assignment. So I kind of approached it as if I'm a documentary filmmaker and I'm gathering footage and I can just draw things. Like there's a pontoon bridge construction sequence, they have the actual construction diagrams from that time at the New York Public Library. So, I just spent a couple weeks drawing them, constructing this crazy bridge. And I didn't know where it fit into my story. And I didn't know what kind of texts would be paired with it. But I had that footage. And so, I could draw that while I was also reading other things and researching other things. And I was still being productive with my time.

So the book is literally a collage, which is also part of why it took so long. It took me years to figure out how to put it into a 300-page thing that had some kind of beginning, middle and conclusion and kind of a key thing to unlocking it, was deciding to spend a lot of time back with the sister with the Quakers. There's one chapter of the book that has basically no text that's suggesting things that are going on with the sister that she isn't writing in the letters. And it's really almost a wordless comic right there. When I got that one, that kind of helped me unlock making it. Because I basically quit. I thought, this book has no story. I spent years working on this thing. I had quit before I figured out those kinds of things.

In Cryptozoo there’s a brief storming-the-Capitol kind of scene. That was something that might not have even seemed like a possibility when you started making this in 2014.

We had recorded Michael Cera saying that in 2017, and then the movie came out in January at Sundance. So, it was totally bizarre, of course. You make your story and you make it in your time to the best of your ability, and then the audience completes it in their time in their mind. And when you have something like that, you realize how much you're handing it over to an audience, because it was completely unexpected and not intentional on my part, of course.

Discipline is about the Civil War. You don't show a lot of Confederate imagery, but there's a moment when we see that flag. There's this question that runs throughout the entire text as to when violence is justified, which also came up last summer during the Black Lives Matter uprisings. Throughout the South, there's been this questioning of the history of the Civil War and the way that that's present in people's daily lives. To what extent were you thinking about the potential timeliness of the book when you were working on it?

Well, if anything, it kind of made me think to not do the book. So, that kind of contributed to the self-doubt. Because I obviously was attracted to this material from living here. Growing up in Richmond, it definitely felt like that it was literally a haunted town in a very real way, that there were unaddressed ghosts in this town. And the events that have happened in the past few years have helped Richmond in some way address these ghosts that are still here. But thinking about how timely something is is totally futile. And I'm a naturally impatient person and I would love to make things quickly and kind of respond. But the medium is not built for that. During Cryptozoo, it felt so far removed from what was going on that I remember telling Jane and Emily, "Our movie will suddenly become relevant when a unicorn is found, a week before our movie comes out."