A few months ago, Friend of Screen Slate John Klacsmann shared a tweet that generated concern among a small but significant group of archivists, filmmakers, and curators: “@Kodak discontinuing color internegative stock (the most used stock when preserving 16mm experimental films) with no notice is a very 2020 move”

Wanting to know more, I reached out. In addition to being friends, Klacsmann and I are colleagues. He’s the archivist at Anthology Film Archives, where he conducts preservation on countless underground, experimental, amateur, and artist-made films. This often intersects with my own job as Technical Director at Electronic Arts Intermix, where I oversee artists’ video preservation. Among the artists whose work we both preserve across our institutions and in their respective film/video formats are Carolee Schneemann, Jud Yalkut, Vito Acconci, Ken Jacobs, and Joan Jonas.

While this conversation is inherently technical, we approached it in a way that should be accessible to readers with little-to-no understanding of film preservation. And it’s worth emphasizing that what we discuss is, in a sense, a “niche” issue tied to specific kinds of films, and has its own workarounds. But it does lead to questions about the direction of film preservation, such as the challenges of scaling the complex industrial processes of producing film stock for reduced demand, and what the actual end might look like. We also discuss some of Kodak’s pivots to other, sometimes curious models including fashion, pharma, and cryptocurrency.

This conversation began over email in December 2020 and has recently been collaboratively edited and updated for publication.

Jon Dieringer: What did Kodak announce?

John Klacsmann: They announced the discontinuation of color internegative stock in both 16mm (stock number 3273) and 35mm (stock number 2273). As far as I know, this was solely announced via a PDF “Discontinuation Listing” on their website.

Let’s start with an obvious first question: does this have anything to do with Kodak becoming an, uh, pharmaceutical company?

Ha! I would guess it isn’t related at all. Kodak has been downsizing their product catalog for many years now. Nonetheless, for some of us, this recent announcement hits hard.

I’m sure you could write about it at great length, but can you briefly explain the significance — most in our field would probably say necessity — of film-to-film preservation? Even in instances where you’re bringing digital steps into your workflow, why is it still ideal to create film negatives and prints?

Well, polyester-based film negatives will last a pretty long time — many, many decades — if stored properly. They’re great “carriers” for the long-term preservation of moving images (whether they were originally shot on film or digital)! In fact, Microsoft recently used what I’m guessing was black & white polyester film to archive a snapshot of all of GitHub in an Arctic vault.

We also usually need to first produce new negatives so that we can make new prints for screening and exhibition purposes. I hope it is not fringe in 2021 to suggest that showing a film made on film on film makes some sense.

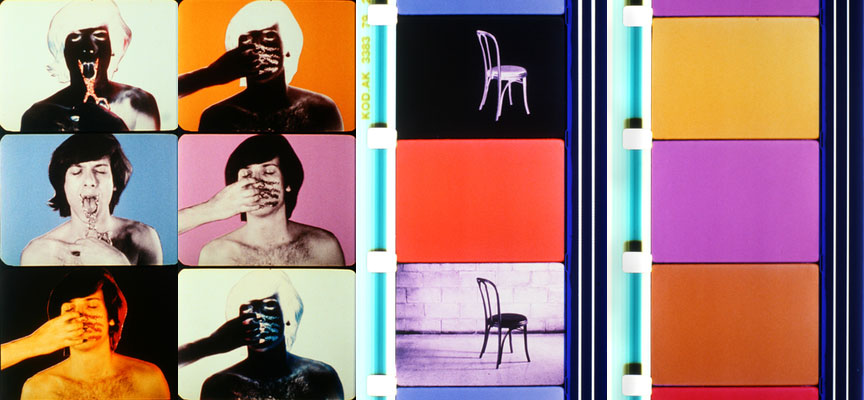

Relatedly, do you think that avant-garde work benefits from film-to-film preservation or exhibition more than other forms? I’m thinking of work where the intermittent motion and flicker of the film projector is key, or things like J.J. Murphy’s Print Generation, which is premised on photochemical processes and their imperfections.

I think a lot of it does. We continue to be dedicated to film preservation and exhibition at Anthology. That being said, I tend to argue for producing new film and digital masters during preservation projects nowadays. If you can, why not do both? But, yes, I think a lot of avant-garde work really lends itself to being preserved and exhibited on film first and foremost. I’m thinking here of Paul Sharits’s work, which is flicker-heavy and often references film projection or the medium of film itself. Print Generation is another great example. It’s literally about film printing, processing, and analog generation loss!

So, what is the Kodak Color Internegative 16mm Film 3273, and why is its discontinuation bad for experimental film preservation? And for people with no film background, can you explain internegative stock? How is it different than other film stocks, like camera or print stock?

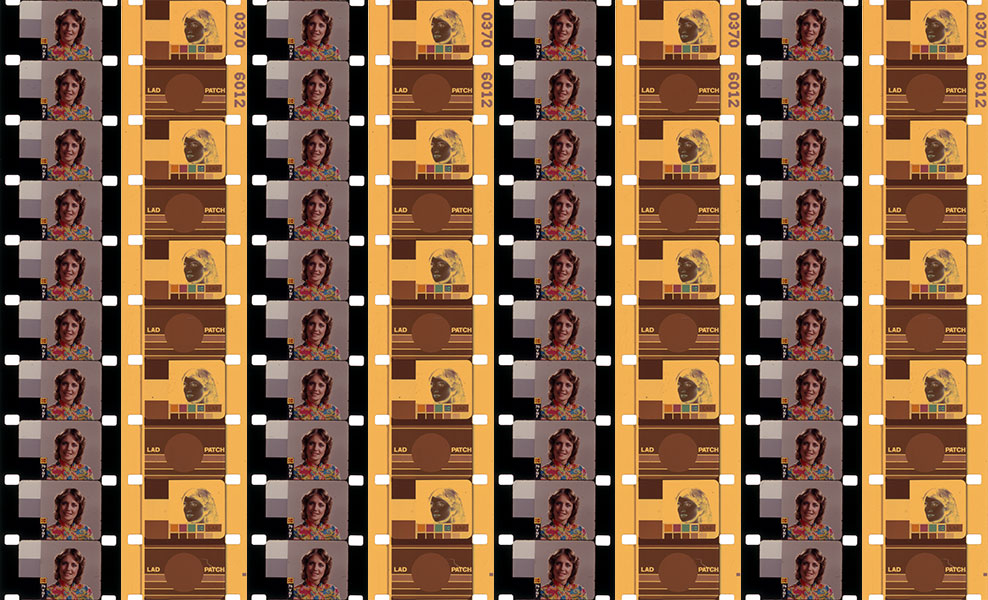

This is a stock that is used when producing archival negatives from original color reversal (e.g. Kodachrome, Ektachrome) films. It is also used in unfortunate cases where a film has to be preserved from a color print. This happens when no better elements, like a camera original, survive.

A lot of experimental films (and other small gauge films, like home movies) were originally made on color reversal films. Therefore, this is the stock I use most often when preserving 16mm color films at Anthology. Of course, we’ll make new prints off of these new internegatives as part of that preservation process too. Essentially, this is the stock we use in the process of preserving and making new prints of a lot of historic 16mm color experimental films. Other people heavily invested in the preservation of 16mm film would rely on this same internegative stock as well.

Kodak discontinues film stocks somewhat regularly, including well-known ones like Kodachrome and Ektachrome in the past. (It’s my understanding that Ektachrome is back?) Could you speak to some of those, and how they’ve changed avant-garde filmmaking and film preservation?

Yes, strangely, Ektachrome is back after being briefly discontinued for several years. At a conference, the Kodak reps tried to get me excited about this by telling me, “John, it’s so great! You’ll love the new Ektachrome! It is low saturation!” I think they were a little crushed when I immediately told them that was what had been so good about Ektachrome! It had HIGH color saturation! Psychedelic, man! I was a little sad that they didn’t seem to understand their own product line.

Kodachrome and Ektachrome are camera films, so while it really sucks for filmmakers and artists when Kodak discontinues camera stocks, generally speaking it has very little to do with film preservation. We’re using different stocks in the film preservation process — stocks made specifically for duplicating films at a lab, not for shooting them in a camera. The now-discontinued internegative stock was one of those duplicating stocks. It’s a big loss for film preservationists.

Is Kodak producing other color interneg stock? If so, what’s special about the 2273/3273? And if not, what is the alternative?

JK: While they have not discontinued other color film preservation stocks — stocks made for duplicating/preserving films shot on negative — their announcement was that they are completely discontinuing the color internegative stock, both 2273 (35mm) and 3273 (16mm). So, for those of us primarily preserving films originally shot on reversal film stocks, this is a big deal. Again, this is a stock commonly used to preserve avant-garde films, documentaries, and home movies and it’s been available for many decades in some form (previously 7271, 7272, and 3272, for example).

But rest assured, this is not “game over.” Moving forward, it looks like we’ll be forced to use color camera negative stock to make internegatives. This is not an ideal substitute. Currently, Kodak only makes their 16mm camera stocks in 100ft and 400ft lengths (about 11 minutes at 24fps). Hopefully they’ll at the very least make it in longer 2,000ft lengths (about 55 minutes at 24fps) so we can use this camera stock to duplicate longer films. We can then make new prints off of these negatives.

The slowest speed color negative camera stock is basically the same as the discontinued internegative except for one critical detail: it is on acetate base, not polyester. Acetate film is not as good long-term as polyester. At least for the last several decades, when a film is “preserved,” polyester stocks are used. “Vinegar Syndrome,” which is acetate base decomposition, is a serious archival issue. We don’t have to worry about that with polyester-based film elements. So, it is not great to now be forced to make some of our archival negatives on acetate camera stock. It is a step backwards, basically.

Are there other companies producing color interneg?

Nope. Kodak is the only producer of any type of color negative motion picture film. In fact, Kodak invented what we now know as color negative/positive film and they’ve continually refined that product since the 1950s. I’m skeptical that anyone else will be able to produce comparable color negative stocks now or in the future, no matter the type: camera stocks or preservation stocks.

What do you see as being the final nail in the coffin for avant-garde film (-to-film) preservation? Is there a particular stock where it’s like, well, that’s it, we’re Anthology Video Archives now?

Good question. Well, going back to my previous answer, when Kodak stops making color negative and/or color positive print stock completely, it’s probably game over for color film-on-film preservation. I don’t see any other manufacturer stepping in to fill the gap. That wouldn’t mean the end of Anthology Film Archives (we have thousands of films in the collection and archive digital video too), but it would mean the end of producing archival negatives and preservation prints of color films as we have for the last 50 years.

Have you spoken to others in the lab and preservation business about this? What’s the general reaction?

JK: Only a few people at film labs. I just became aware of the internegative discontinuation last December; it was a recent — and sudden — announcement.

How worried should people in the preservation community be? What about Screen Slate readers? Do you see this having an effect on loaning and screening prints? For instance, does it have the potential to make damaged prints riskier or impossible to replace, encouraging lenders to restrict their access?

Well, again, this is not “game over,” but some film-to-film preservation will now be harder, inferior in some ways, and more expensive. This is a trajectory we’ve been on for a while. Still, this recent announcement is not good news. For now, we can still produce new color prints from color negatives, so I don’t think it affects the production or loaning of film prints much. That being said, it has been expensive and time consuming to replace film prints for a while now.

What is your sense of the challenges for Kodak to continue making film stock? I’m guessing that it’s a hugely complex process that involves a lot of chemicals and machinery and a scale that can’t be simply replicated — like, if someone were gifted the patent to Kodachrome and some start-up capital, they couldn’t simply crank it out in artisanal small batches.

Yeah, Kodachrome is not coming back, unless Kodak does it, and that’s not going to happen. It’s a complex film with involved processing. Kodak invented and refined color negative/positive film stock, and they’ve been making it longer and better than anyone for many decades. I just don’t see anyone successfully taking on manufacturing of color film. Black and white film, however, is much simpler and there is already at least one other major film manufacturer for it, ORWO. Thank God!

I think there is probably a pretty stable — but small — group of consumers for most of Kodak’s product line, including the internegative stock. If Kodak was able to tweak their production lines to produce smaller batches that would probably help the economics of it all. But that’s probably easier said than done. They’ve long been set up for the truly mass production of film stock. Many New York City film labs closed years ago for this reason: they were built for a large workload they didn’t receive anymore. It was impossible for them to downscale, so they had to close.

Some people have identified The Impossible Project as a potential model. They were founded after Polaroid announced they would no longer produce film for their instant cameras, and a new business was able to buy or lease a lot of their assets to continue to make product. Long story short, The Impossible Project basically usurped Polaroid and was able to acquire everything and has literally rebranded as Polaroid. Is there a reason that couldn’t happen with Kodak?

I don’t know all the details of the Impossible Project. I’m assuming it requires much larger production facilities and more labor to produce motion picture film. Instant film is complex but you’re making a massive amount of stock when making motion picture film when compared to still photography. I mean, if someone bought Kodak Park in Rochester and hired all the Kodak staff, maybe it could be spun off into a new business similarly, but I think the larger issue is still downscaling the production lines.

So we know about the whole Kodak-Trump pharma thing and insider trading questions. Let’s talk about some other weird stuff. There’s the Super 8 camera that doesn’t seem to really exist. There’s KodakCoin cryptocurrency and the Kodak KashMiner. There’s their defunct movie listings app that cited Screen Slate — the least profitable business in the history of time — in their initial outreach to theaters here in NYC. And perhaps most successfully there’s an actually kind of cool if sweatshop-y clothing line licensed to Forever21 and another line with Opening Ceremony. Am I forgetting anything? What is going on there?

I think besides the bad business decision to buy a pharmaceutical company in the late 1980s, that pretty much sums it up. Well, I guess they also did some collaborations with Girl Skateboards a few years back? But, yeah, I wish I had more insight into their business decisions, which often baffle me. I’m always available to them as a consultant! I will say I have enjoyed picking up some stylish vintage-inspired Kodak t-shirts in recent years. They’re very cool as a fashion company.

For sure, I just picked up a vintage Kodak fanny pack. Anyway, Kodak has been hit tremendously by the digital sea change, and there’s an argument to be made that we’re lucky they continue to exist at all. At the same time, people who are cheering them on and whose livelihoods as artists and conservators depend on them seem like they’re occasionally confounded and exasperated. But we want them to win. Do you have any thoughts as to what we can do?

Yeah, Kodak is the company we all love to hate sometimes. But, yes, deep down we all want them to succeed. We love working with film, we appreciate watching film prints, and we understand what a wonderful archival medium film is. As cheesy as it sounds, we’re loyal customers. I think that’s why we can’t help but be frustrated year after year as Kodak’s product catalog slowly implodes.

I think we can bring attention to the (sometimes nuanced) issues here and hope it gets through to them — that their business decisions do have cultural repercussions. I want to be optimistic but it is really hard. I suppose the best strategy is to continue to preserve film on film while we still can. It’s getting harder and harder and we won’t be able to do it forever.